What if you could select from a menu to create an effective personalized “recipe” for treating each youth receiving psychotherapy? By adding in the right “ingredients,” in just the right doses, a clinician might be able to create an individually tailored “meal” to treat each individual young person. This personalization is an aim of modular youth psychotherapy, which provides a menu of treatment elements from which therapists select a distinctive combination and permutation for each child or adolescent. Modular youth psychotherapies are increasingly popular, in part because their flexibility facilitates personalizing, but the clinician decision-making required can be complex. In this scoping review, we assessed the guidance provided to clinicians in modular youth psychotherapies as they select personalized modules and treatment targets.

What if you could select from a menu to create an effective personalized “recipe” for treating each youth receiving psychotherapy? By adding in the right “ingredients,” in just the right doses, a clinician might be able to create an individually tailored “meal” to treat each individual young person. This personalization is an aim of modular youth psychotherapy, which provides a menu of treatment elements from which therapists select a distinctive combination and permutation for each child or adolescent. Modular youth psychotherapies are increasingly popular, in part because their flexibility facilitates personalizing, but the clinician decision-making required can be complex. In this scoping review, we assessed the guidance provided to clinicians in modular youth psychotherapies as they select personalized modules and treatment targets.

Just as one child in need of Vitamin C might receive orange juice to drink with their dinner and another who could use more calcium might drink milk, a particular module might work optimally for one child, but prove less effective for another – based on a variety of factors. As an example, consider a young client with social anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, a heart condition, and a single parent who is skeptical about the value of psychotherapy. All these variables might impact optimal treatment selection. Adding to the complexity, client problems, preferences, and needs often change during treatment. Multiple real-life events that occur unpredictably throughout treatment can affect which module may be most needed when.

Decisions about which problems to target in treatment, and which modules to use may depend on a complex array of variables. What is the clinician’s expertise and experience? How long do they expect treatment to last? Do the youth and caregivers have module and treatment target preferences? Which problems does the clinician see as most severe and impairing? When should a module be selected? For how many sessions should the module be used? These questions may all guide decision-making, and answering them can often be difficult. We assessed the decision guidance present in 20 existing modular youth psychotherapy protocols described in 67 journal articles.

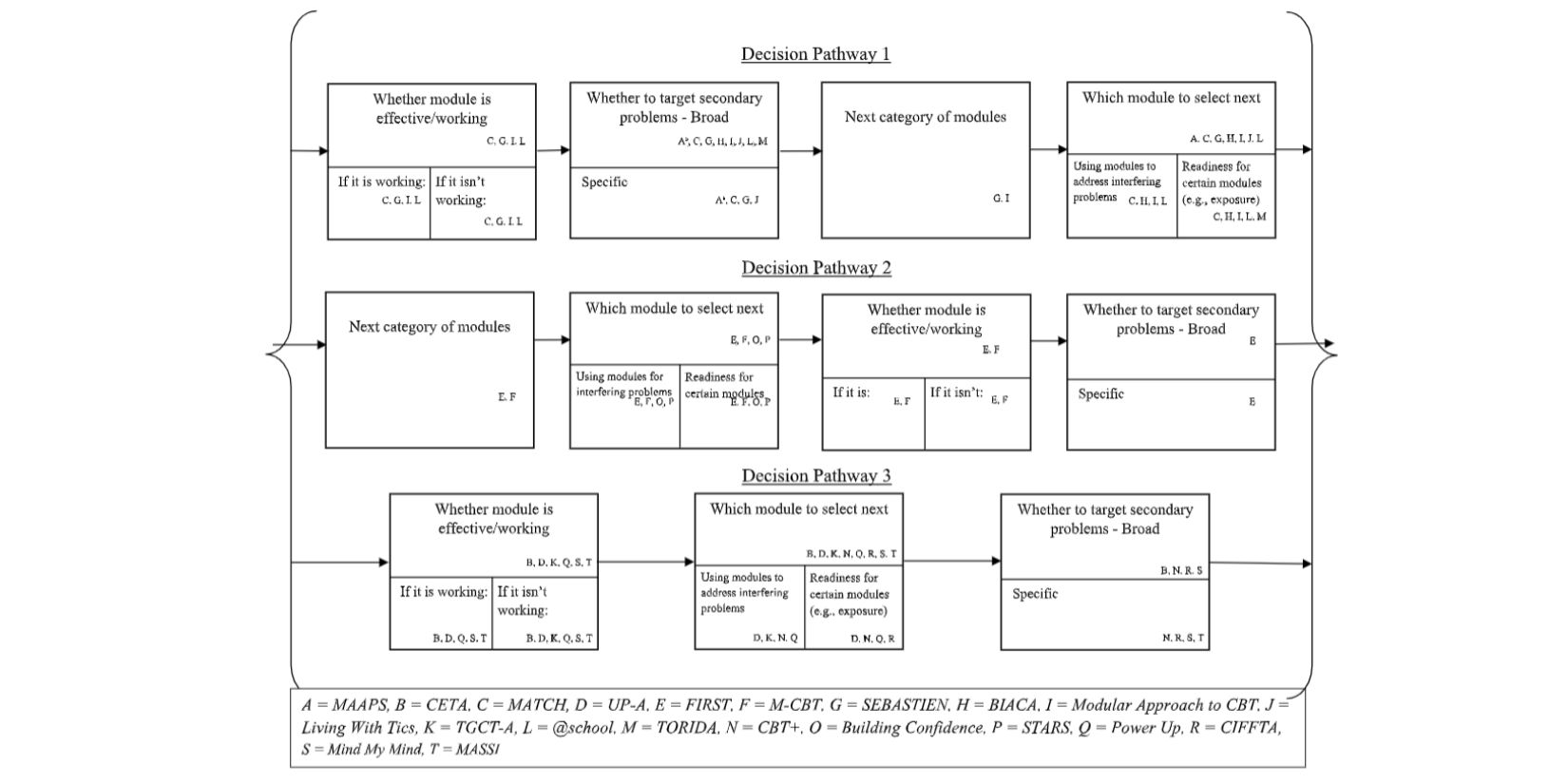

Figure 1.

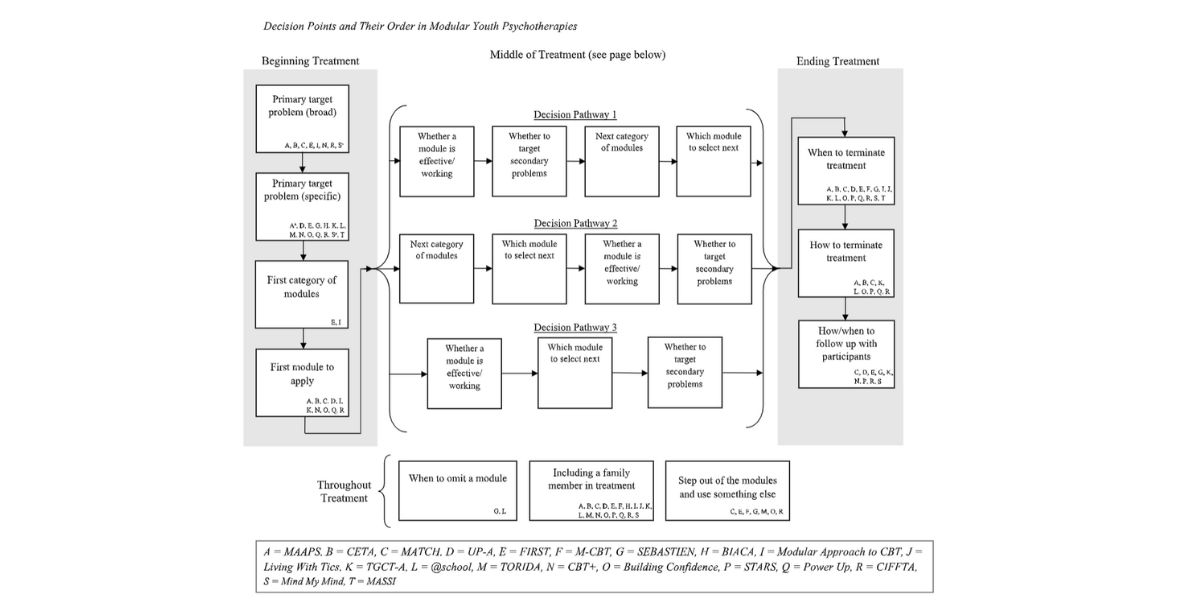

First, we found that, just as a standard meal might include at least a drink and a main course, most protocols included a few recommended or required modules. Most commonly, modular youth psychotherapies featured:

- A required/recommended assessment or introductory module

- A required treatment wrap up module

- One or several core modules (e.g., exposure) intended to be received by all participants

Additionally, most modular psychotherapy protocols encouraged decision-making about modules throughout the treatment process. However, a quarter of protocols featured decision formulations made primarily at the beginning of treatment, with the ability to flexibly shift these decisions throughout therapy– for example, with a meeting to set personalized modules before treatment begins, followed by adaptations throughout depending on client progress.

All modular youth psychotherapies recommended using clinical judgment when making decisions. Many also included narrative descriptions of modules or flowcharts to guide decisions. A few recommended seeking input from clients and one used an algorithm with a replicable process and outcomes (e.g., based on scores on symptom measures, an algorithm would recommend treatment targets). Despite evidence that statistical models of archival data outperform clinical judgment, no modular psychotherapy used statistical models of archival data to guide decision-making. Maximizing therapy effectiveness may require building decision supports that incorporate client perspectives and balance clinical judgment with statistical methods.

Figure 2.

Building a science of personalization in youth modular psychotherapy will likely involve much future research on which modules, in which combinations and permutations, and at which points in therapy, work best for youths with which personal and clinical characteristics. This will likely go alongside research on which decision-making guidance tools are associated with optimal decisions and client outcomes. Our scoping review aimed to identify common decision-points across modular youth psychotherapies (see figures for flowcharts of existing decision points). We hope that these findings may help guide future clinical work and research to better ensure that young people receive the most personalized and effective treatment course possible.

Discussion Questions

- To what extent do you think clients should provide input on their treatment plan?

- Some therapies provided a lot of structure to constrain module choices, some provided moderate structure, while others provided near complete flexibility in decision making. What do you think might be the optimal balance of flexibility and structure in clinical decision making?

- There is evidence that statistical models outperform clinical judgment, yet statistical models of treatment data are not often used to recommend treatment decisions in modular youth psychotherapies. Why might this be?

- What do you think is the best way to combine clinical judgment and guidance from statistical models? In what ways, if at all, would you ideally like to incorporate statistical models into your clinical decision-making?

Reference Article

Venturo-Conerly, K., Reynolds, R., Clark, M., Fitzpatrick, O., and Weisz, J. “Personalizing Youth Psychotherapy: A Scoping Review of Decision-Making in Modular Treatments.” https://doi.org/10.1037/cps0000130

About the Authors

Katherine Venturo-Conerly, MA: Katherine Venturo-Conerly completed her undergraduate training in psychology and global health at Harvard College in 2020, before matriculating to the Harvard clinical science PhD program that same year. She now works in the Lab for Youth Mental Health under Dr. John Weisz, where she studies youth psychotherapy design using multiple methods in contexts both domestically and abroad. Venturo-Conerly can be contacted at kventuroconerly@g.harvard.edu.

Katherine Venturo-Conerly, MA: Katherine Venturo-Conerly completed her undergraduate training in psychology and global health at Harvard College in 2020, before matriculating to the Harvard clinical science PhD program that same year. She now works in the Lab for Youth Mental Health under Dr. John Weisz, where she studies youth psychotherapy design using multiple methods in contexts both domestically and abroad. Venturo-Conerly can be contacted at kventuroconerly@g.harvard.edu.

- Rachel Reynolds, AB: Rachel Reynolds completed her undergraduate training in psychology at Harvard College in 2022, working as a research fellow with the Weisz Lab for Youth Mental Health. Rachel is currently a Post-Baccalaureate Fellow at McLean Hospital, where she works as a Community Residence Counselor at the OCD Institute for Children and Adolescents. Reynolds can be contacted at rlreynolds470@gmail.com.

- Malia Clark, AB: Malia Clark completed her undergraduate training in psychology and French at Harvard College in 2021. She is an associate at Global Health Strategies, a communications and advocacy organization. Clark can be contacted at itsmalia.clark@gmail.com.

- Olivia Fitzpatrick, MA: Olivia Fitzpatrick completed her undergraduate training in psychology at The Ohio State University in 2017, after which she managed a research program and clinic at UCLA designed to implement brief interventions for adolescents at risk for suicide. Currently, Olivia is a doctoral candidate in clinical science in the Lab for Youth Mental Health, with a specialization in understanding ways to improve access to and the effectiveness of youth psychotherapies. Fitzpatrick can be contacted at ofitzpatrick@g.harvard.edu.

- John Weisz, PhD, ABPP: John Weisz is Professor of Psychology in the Harvard Psychology Department and in Harvard Medical School. He directs the Harvard Lab for Youth Mental Health, where he and his students and colleagues work to improve mental health care for children and adolescents. They develop and test interventions, and they conduct meta-analyses characterizing the state of knowledge and proposing ways to improve the science of youth mental health. Dr. Weisz can be contacted at john_weisz@harvard.edu.