The movement for prescriptive authority for psychologists, RxP, has been controversial within and outside of the profession, and slow to gain traction. Over three decades, debates have centered around the quality of training (McGrath, 2020; Robiner et al., 2020), patient safety, and motivations for pursuing RxP. The American Psychological Association (APA) promoted RxP to address a long-known shortage of psychiatrists. A generally overlooked consideration has been the workforce capacity of prescribing psychologists in comparison to all other prescribers. How might limitations in the workforce of prescribing psychologists limit the overall impact and viability of RxP?

Limited Impact to Improve Access to Care

Survey data reveal RxP is controversial within psychology and that prescribing psychologists wouldn’t practice in large numbers in medically underserved (e.g., rural) areas (Baird, 2007; Tompkins & Johnson, 2016). Hughes and colleagues’ (2024) study of de-identified, employer-sponsored insurance claim data from over 255 million individuals, including in New Mexico and Louisiana, two of the first states to pass RxP legislation two decades ago, revealed a greater proportion of patients treated by prescribing psychologists lived in metropolitan areas. Despite APA’s continued advocacy for RxP, the small number of psychologists pursuing prescriptive authority limits their impact offsetting the shortage of psychiatrists.

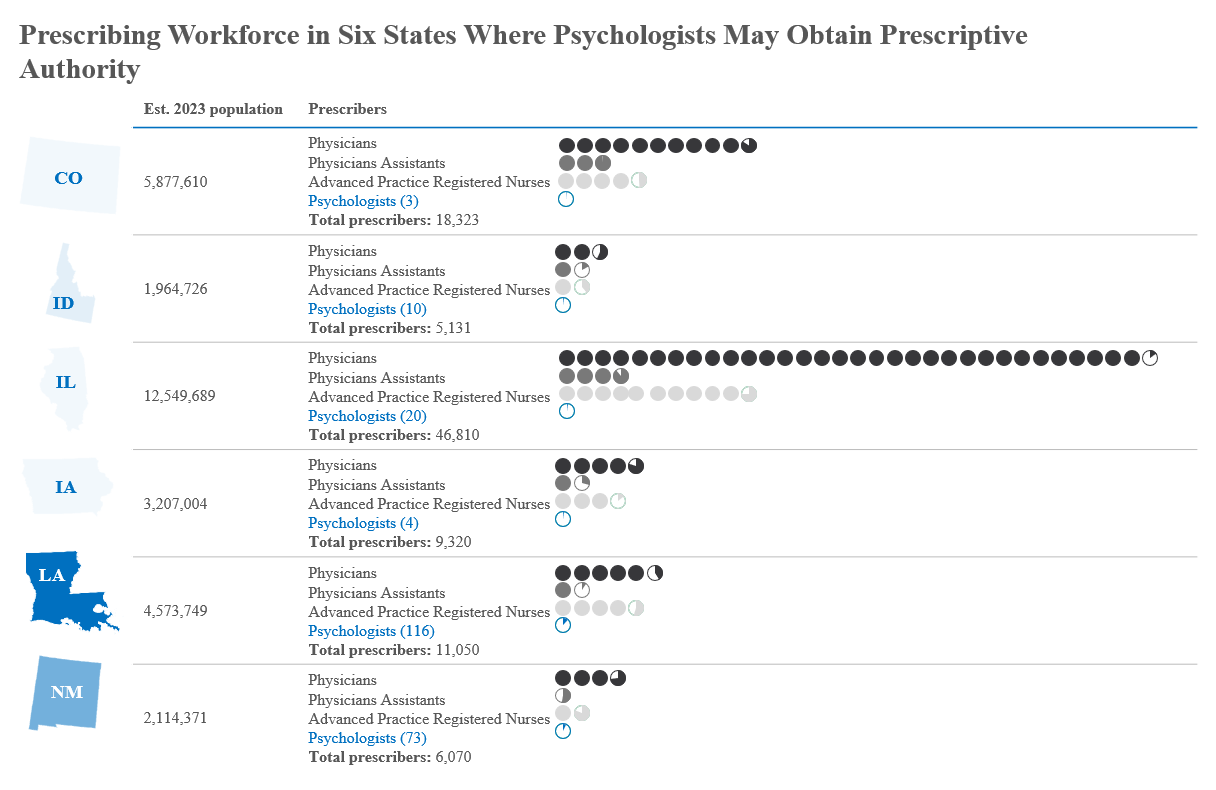

As of March 2024, only 226 psychologists across six states were licensed to prescribe. Utah passed RxP legislation later in 2024, so was not included in our analysis. This figure is strikingly modest and reflects a slow increase over the past decade, averaging »12.5 additional prescribing psychologists per year. This represents just 0.14% of the Association of State and Provincial Psychology Board’s (ASPPB’s) estimate of 156,087 licensed psychologists in the U.S. Even in New Mexico and Louisiana, prescribing psychologists comprise only 8.17% and 14.8%, respectively, of licensed psychologists in those states after two decades of allowing it.

(click to enlarge)

Bigger Picture: Other Professions Are Filling the Gaps

Prescribing psychologists represent only 0.23% of the workforce of all prescribers in states where psychologists can prescribe, raising questions about the effectiveness of RxP in bridging gaps in psychoactive pharmaceutical care. Other professions are increasing prescribers in more meaningful numbers. More medical schools have opened. Psychiatric residency programs expanded from 183 in 2011 to 352 programs in 2022. These are the most direct developments ameliorating the psychiatrist shortage.

Other health professions have been filling gaps in psychiatric care. Physicians in other specialties now receive more psychoactive prescribing training than when RxP was first conceived. Nurse practitioners (APRNs) and physician assistants (PAs) have training more closely aligned with prescribing than psychologists do. Their workforces are growing faster than the workforce of prescribing psychologists. They have more training programs poised to train yet greater numbers of prescribing professionals. The number of psychiatric NPs more than doubled in recent years, outnumbering prescribing psychologists by a wide margin. PAs also have seen significant workforce expansions, with prescriber-to-population ratios exponentially higher than that of prescribing psychologists. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) predicts greater growth of these professions in coming years than is anticipated for psychologists. In Louisiana and New Mexico, the ratio of prescribing psychologists to the population is about one one-hundredth of the rates for other prescribers. Clearly, other professions are better prepared to effectively address prescriber shortages and are more substantively doing so.

Is the RxP Movement Worth the Investment?

Given the small number of prescribing psychologists and the high costs associated with advocating for RxP, it is reasonable to question whether the RxP movement is a worthwhile investment. APA and state associations have spent millions of dollars lobbying for prescriptive authority, but the return has been relatively minimal: hundreds of failed legislative efforts and only seven states passing prescribing laws. Moreover, relatively small minorities of psychologists have sought to prescribe where they have been able to. The impact of RxP in creating tensions between psychology and other prescribing professions is evident, if difficult to gauge.

From a workforce perspective, it is not clear that RxP will ever achieve the kind of momentum that could make a meaningful difference in addressing the nation’s pharmacological mental health needs. The numbers to date plainly do not support the ideas that prescribing psychologists play a major role in expanding access to psychopharmacological care, nor that they will in the future.

Building a Collaborative Future That Stays True to Psychologists’ Roots

McGrath (2004) identified factors he believed could guard against prescribing psychologists’ over-reliance on psychotropic medications observed in other professions’ prescribers. These included psychologists’ strong training in psychosocial treatments and research, growing cultural skepticism regarding the effectiveness of medications, and an academic community questioning their appropriate use (e.g., Hollon, 2024). However, studies (Levine et al., 2011; Linda & McGrath, 2017; Peck et al., 2021) in which most prescribing psychologists reported prescribing medication to the majority of their patients, both as monotherapy and in combination with psychotherapy, raise questions about McGrath’s (2004) contention that prescribing psychologists would stay true to their “psychological souls” and be more conservative about prescribing and about polypharmacy because of their prior psychological training.

It is time to pivot psychology’s focus to collaborative care models. Psychologists are well-equipped to work alongside psychiatrists and other physicians, nurse practitioners, and PAs in interdisciplinary teams. By leveraging their strengths in psychological assessment, psychotherapy, consultation, and research, psychologists are well-positioned to contribute to comprehensive patient care that addresses both psychological and pharmacological needs.

Since the APA adopted RxP as policy, workforces of physicians, ARNPs and PAs have more effectively expanded to improve patient access to psychoactive medications. With significant projected growth in these professions, they are expected to fill gaps even more successfully than small numbers of prescribing psychologists. It would be more beneficial for psychology to focus efforts and resources on goals that align with its core strengths, and that benefit the greater community of psychologists, rather than continuing to chase the controversial, divisive, and costly pursuit of prescriptive authority for a small fraction of psychologists. From workforce and policy standpoints, is RxP a case of the tail wagging the dog?

Reference/Target Article

Robiner, W. N. & Tompkins, T. L. (2024). The workforce of prescribing psychologists: Too small to matter? Worth the cost? Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/cps0000253

Discussion Questions

- If such a small minority of psychologists obtain prescriptive authority, does it meaningfully ameliorate the shortage of psychiatrists it was intended to address?

- The APA elected not to create psychopharmacology training for psychologists for Level 2 (Collaborative Practice; consultation-liaison model) as described by APA Ad Hoc Task Force on Psychopharmacology (Smyer et al., 1993). Instead, it focused on Level 3 (Prescription Privilege) in which psychologists could prescribe. Would level 2, in which psychologists develop a knowledge base for actively working with licensed prescribers to manage medications but do not prescribe themselves, be a way in which psychologists could more safely and meaningfully contribute to psychopharmacological care?

- What are the other costs to the profession of pursuing RxP?

- Are the small numbers of prescribing psychologists in the mainstream of the profession or are they outliers?

- Given how few psychologists prescribe, the vast number of other types of prescribers, the volume of psychoactive medications prescribed in the US, and advances in telehealth and models of collaborative care, is RxP justified?

About the Authors

William N. Robiner, Ph.D., A.B.P.P. completed his training in Clinical Psychology at Washington University and internship at the University of Minnesota Medical School. He is a Professor and Director of Health Psychology at the University of Minnesota Medical School, has served as director of its psychology internship and Clinical Health Psychology postdoctoral fellowship, and has written about the psychology and mental workforce and about prescriptive authority for psychologists. He served on the ASPPB Education and Training Committee that reviewed prescriptive authority, proposed the name of the Psychopharmacology Examination for Psychologists (PEP), and has been active in Psychologists Opposed to Prescription Privileges for Psychologists (POPPP; https://www.poppp.org).

William N. Robiner, Ph.D., A.B.P.P. completed his training in Clinical Psychology at Washington University and internship at the University of Minnesota Medical School. He is a Professor and Director of Health Psychology at the University of Minnesota Medical School, has served as director of its psychology internship and Clinical Health Psychology postdoctoral fellowship, and has written about the psychology and mental workforce and about prescriptive authority for psychologists. He served on the ASPPB Education and Training Committee that reviewed prescriptive authority, proposed the name of the Psychopharmacology Examination for Psychologists (PEP), and has been active in Psychologists Opposed to Prescription Privileges for Psychologists (POPPP; https://www.poppp.org).

Tanya L. Tompkins, Ph.D. completed her training in Clinical Psychology at UCLA and the Neuropsychiatric Institute and Hospital at UCLA. She is currently a Professor of Psychology at Linfield University where she engages undergraduate students in research, with a focus on science-based prevention and stigma reduction. She has conducted research and written about prescriptive authority for psychologists and is an active member of Psychologists Opposed to Prescription Privileges for Psychologists (POPPP; https://www.poppp.org). Dr. Tompkins can be contacted at [email protected].

Tanya L. Tompkins, Ph.D. completed her training in Clinical Psychology at UCLA and the Neuropsychiatric Institute and Hospital at UCLA. She is currently a Professor of Psychology at Linfield University where she engages undergraduate students in research, with a focus on science-based prevention and stigma reduction. She has conducted research and written about prescriptive authority for psychologists and is an active member of Psychologists Opposed to Prescription Privileges for Psychologists (POPPP; https://www.poppp.org). Dr. Tompkins can be contacted at [email protected].

References Cited

Baird, K. A. (2007). A survey of clinical psychologists in Illinois regarding prescription privileges. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 38(2), 196–202. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.38.2.196

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, (2024). Occupational outlook handbook. Retrieved March 5, 2024, from https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. (2024). Occupational outlook handbook. Nurse anesthetists, nurse midwives, and nurse practitioners. Retrieved March 5, 2024, from https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/nurse-anesthetists-nurse-midwives-and-nurse-practitioners.htm

Hollon, S. D. (2024). What we got wrong about depression and its treatment. Behavior Research and Therapy, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2024.104599

Hughes, P. M., McGrath, R. E., & Thomas, K. C. (2024). Simulating the impact of psychologist prescribing authority policies on mental health prescriber shortages. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 55(2), 140-150. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000560

Linda, W. P., & McGrath, R. E. (2017). The current status of prescribing psychologists: Practice patterns and medical professional evaluations. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 48(1), 38-45. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000118

McGrath, R. E. (2004). Saving our psychosocial souls. American Psychologist, 59, 644–645. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.644

McGrath, R. E. (2020). What is the right amount of training? Response to Robiner et al. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 27 (1), e12315. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12315

Peck, K. R., McGrath, R. E., & Holbrook, B. B. (2021). Practices of prescribing psychologists: Replication and extension. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 52(3), 195–201. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000338

Robiner, W. N., Tompkins, T. L., & Hathaway, K. M. (2020). Prescriptive authority: Psychologists’ abridged training relative to other professions’ training. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 27(1), e12309. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12309

Tompkins, T. L., & Johnson, J. D. (2016). What Oregon psychologists think and know about prescriptive authority: Divided views and data-driven change. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research, 21(3), 126-161. https://doi.org/10.1111/jabr.12044