APA Student Poster Award Winner Rachel Zachar shares her research at Nova Southeastern University, where she is a doctoral student.

The Angry Brain

As expected, behavioral outbursts are one major outcome expected to be seen from individuals who experience high levels of self-reported anger. Moreover, effects on cognition with regards to the presence of anger have not been as heavily considered as compared with behavioral understandings and treatments for anger. What effects might anger have on the brain and what might these mean in clinical and health related settings?

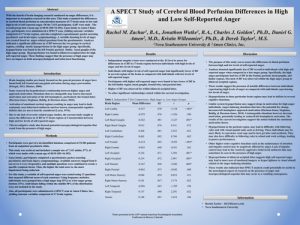

Behaviors such as yelling, screaming, and physical violence may be some of the several potential outcomes after anger provocation. But what is actually going on inside of the brain that leads to these outbursts? The current investigation sought to answer this very question. Activation of emotional cortical regions resulting in anger may lead to less known consequential cognitive deficits that are not as heavily considered (Luria, 1976). Due to the lack of severity-related anger studies, the current study sought to assess the differences in cerebral blood perfusion in 17 brain regions at Concentration between high and low levels of self-reported anger. The current investigative study also focused potential neuropsychological sequelae that result from the presence of high anger.

Participants were part of a de-identified database comprised of 19,384 patients from an outpatient psychiatric clinic. This study was archival and included a sample size of 7,413 adults who upon intake, completed a questionnaire packet assessing psychiatric and brain injury symptomatology. Available answers ranged from 0 (never) to 4 (very frequently), and multiple questions were combined to create a specific symptom factor. Thus, the higher the total score is, the more impairment being endorsed.

For this study, a variable of self-reported anger was created using 13 questions that targeted different areas of each construct. Using frequency statistics, individuals were grouped into a high anger (top 25%) or a low anger group (bottom 25%). Individuals falling within the middle 50% of the distribution were not included in the study. Also, all participants were administered a SPECT scan at Amen Clinics, Inc., yielding outcome variables comprised of 17 brain regions.

Results showed that participants with higher self-reported anger were found to have lower blood flow in the left limbic region, basal ganglia, frontal lobe, and parietal lobe. Higher levels of blood flow were observed for within bilateral occipital lobes. No other significant relationships were observed outside of these results.

What does this all mean in terms of clinical and health impressions? Individuals with high levels of anger tended to have dysfunction or abnormal blood flow in certain regions of the brain that are heavily involved in important cortical functions. Lower levels of blood flow within the basal ganglia may lead to deficits in movement that may not normally be present within individuals with lower levels of anger. Because lower levels of blood flow were observed in this area, it could be possible to see movement difficulties within these individuals, making them seem disoriented. Clinically, these individuals may have a tough time moving smoothly, making otherwise simple movements difficult, such as writing and walking.

Limbic system dysfunction may also lead to other poor emotional outcomes over and above the presence of anger. These individuals may experience other types of negative emotions mediated by the limbic system more readily such as fear. Furthermore, they may be more prone to developing anxiety disorders and other disorders that are heavily influenced by the limbic system, creating a plethora of psychiatric symptoms.

Lower levels of blood flow in the parietal region, may lead to difficulty with following rules and with visual-spatial tasks such as driving. These individuals may be more likely to experience road rage and in turn get into road accidents. They may also have difficulty in following rules in school and work settings, leading to poorer performances.

Other higher order cognitive functions such as the maintenance of attention and impulse control may be negatively affected by anger. Lack of impulse control may lead to the reactively aggressive behavioral outbursts that may sometimes be seen in the presence of high anger.

Higher levels of cerebral blood flow in bilateral occipital lobes suggests high self-reported anger may lead to more uses of emotional imagery or hypervigilance to visual stimuli related to the anger-inducing situation.

Overall, this investigation suggests that individuals with higher levels of anger may not only experience behavioral outbursts in reaction to the anger, but more underlying cognitive deficits as a result of anger. These findings may aid in being able to understand the thinking and actions of individuals with high anger, as well as the deficits that may also accompany them. Knowing these changes may allow for better interventions and treatments to take place to not only aid in decreasing behavioral outbursts, but to also decrease the accompanying cognitive deficits that lead to poorer clinical, health, academic, and vocational outcomes.

About the Author

Rachel M. Zachar, M.S., is a 3rd year Clinical Psychology student with a concentration in Neuropsychology at Nova Southeastern University. She will be completing her second practicum specializing in Neuropsychology at Nova Southeastern University. She has previously written a book chapter on intellectual disabilities and one regarding the neurobiology of violence and aggression. She is also currently working on finishing her directed study focusing on cerebral blood perfusion differences between individuals with varying levels of self-reported anger and self-reported anxiety.

Rachel M. Zachar, M.S., is a 3rd year Clinical Psychology student with a concentration in Neuropsychology at Nova Southeastern University. She will be completing her second practicum specializing in Neuropsychology at Nova Southeastern University. She has previously written a book chapter on intellectual disabilities and one regarding the neurobiology of violence and aggression. She is also currently working on finishing her directed study focusing on cerebral blood perfusion differences between individuals with varying levels of self-reported anger and self-reported anxiety.

Click on the image to download her APA Convention Poster

References

Luria, A. R. (1976). The working brain: An introduction to neuropsychology. Basic Books.