Sexism exists in many forms and across different levels: internally (e.g., a girl believing she is not good at math simply because she is a girl), interpersonally (e.g., a supervisor asking the only woman-identified employee to make lunch reservations), and structurally (e.g., a law prohibiting abortion). Studies have found that sexism is associated with poor physical (e.g., premature death) and mental (e.g., depression) health. It’s possible that girls living in places with higher sexism have worse mental health because living in an oppressive environment makes it harder to get better in mental health treatment. Identifying for whom and under what conditions mental health treatments work is critical. In this blog post, I describe a study that my colleagues and I conducted examining whether psychotherapies are less effective for girls in places with higher sexism.

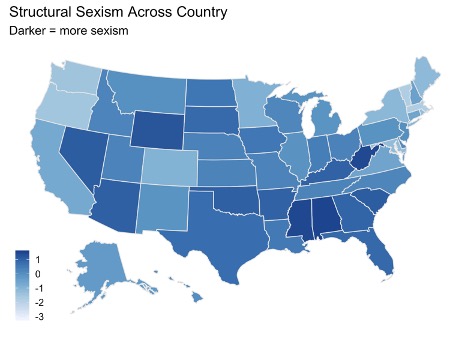

In our study, we wanted to find out whether structural sexism – defined as norms, policies, and laws that create and sustain gender inequality in power and resources – is associated with psychotherapy effectiveness for girls. Using publicly available data on sexist norms (i.e., individual implicit and explicit sexist attitudes) and randomized controlled trial data from youth psychotherapy studies, we conducted a spatial meta-analysis – a novel method for examining how spatial factors (e.g., prejudicial norms, economic inequality) relate to intervention efficacy (i.e., how efficacious an intervention, such as psychotherapy or medication, is). We found that psychotherapies in communities with higher levels of structural sexism were less effective compared to those tested in places with lower sexism. In other words, sexism appears to make it harder for girls to benefit from psychotherapy.

Our findings point to the importance of exploring adaptations to existing psychotherapies that directly address girls’ needs and experiences. Notably, feminist psychotherapy – a therapy approach emphasizing gender – has long asserted that treatment should address gender oppression, and some of its core components are increasingly supported in research. For instance, therapy may be enhanced through:

- An empowering and egalitarian client-therapist relationship

- Discussing stigma: explicitly addressing gender roles, dynamics, and gender-based systems of power and privilege in treatment (e.g., consciousness raising, gender role analysis)

- Incorporating advocacy: Recognizing and taking action against sexism in behaviors, beliefs, and policies (e.g., advocating for policies in clients’ schools to reduce sexist harassment and bullying)

These findings are important for psychologists to consider in research and practice, and highlight the need for structural- and community-level interventions to prevent and respond to internal, interpersonal, and structural sexism at its source. Though future research is needed to better understand the complex interplay between stigma, mental health, and treatment, ours is the first to find that the social context girls live in helps explain the extent to which they benefit from psychotherapy.

Discussion questions

- How can clinicians in communities with high levels of sexism address its influence on treatment and enhance client well-being?

- How might other community-level attitudes (e.g., racism, homophobia, transphobia) impact treatment outcomes for youth with other stigmatized identities?

- How can we reduce sexism in social contexts? Especially those in which girls spend a lot of their time (e.g., schools)?

Target Reference

Price, M., McKetta, S., Weisz, J., Ford, J., Lattanner, M., Skov, H., Wolock, E., & Hatzenbuehler, M. (in press). Cultural sexism moderates efficacy of psychological therapy for girls: Results from a spatial meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. doi: 10.1037/cps0000031

About the Authors

Dr. Maggi A. Price (she/her/hers) is an assistant professor in the School of Social Work at Boston College and director of the Affirm Lab. She studies stigma, trauma, and mental health treatment with an emphasis on transgender and non-binary youth. Dr. Price can be contacted at [email protected] and you can follow her on Twitter @MaggiPrice.

Hilary Skov (she/her/hers) is a School Psychology doctoral student at Tulane University and a member of the Child and Family Lab. She studies how biological factors influence children’s responses to potentially traumatic events, and how social support can promote resilience to these stressors. Hilary can be contacted at [email protected] and you can follow her on Twitter at @CallHerDr.