Self-Care and Professional Impairment Among Licensed Psychologists

By Andrea Lynn Coverman, M.A., LASAC

Introduction:

Until recently, much of the literature linking health care professionals (HCPs) with professional impairment and substance use has been limited to nurses, physicians, dentists, pharmacists, social workers, counselors, and a variety of other healthcare-related disciplines, but not psychologists (Brown, Goske, & Johnson, 2009). The intent of this research was to examine professional impairment and self-care practices specific to licensed psychologists. Professional impairment and self-care were then compared with licensed psychologists’ substance use patterns (i.e., use of Alcohol, Tobacco, Caffeine, and/or Recreational Drug Use). Based on analyses, preventative self-care measures were proposed to reduce the risk of psychologists’ impairment.

Method:

Participants:

The final sample consisted of 358 participants. Participants were licensed psychologists currently practicing in the United States and Canada. The sample consisted of 201 (68.1%) females and 94 (31.9%) males. There were 93 psychologists (26%) from the Northeast, 67 (18.7%) from the Midwest, 63 (17.6%) from the Southeast, 49 (13.7%) from the West, 40 (11.2%) from the Southwest, 19 (5.3%) selected Other (e.g., Canada, Alaska, Hawaii), and 27 (7.5%) did not respond. The racial composition goes as follows: 4 (1.1%) African American, 10 (2.8%) Asian, 321 (89.7%) Caucasian, 15 (4.2%) Hispanic/Latin, 3 (.8%) Multiracial, 3 (.8%) Other, and 2 (.6%) did not respond. Of the total participants, 92 (25.7%) had less than 5 years in practice, 76 (21.2%) had 5-10 years, 65 (18.2%) 11-20 years, 63 (17.6%) 30+ years, 49 (13.7%) 21-30 years, and 13 (3.6%) did not respond. In response to primary setting, 185 (51.7%) psychologists reported working in a private practice, 39 (10.9%) within community healthcare/hospital, 29 (8.1%) in an outpatient clinic, 26 (7.3%) in both educational/school and in government/military/veteran settings, 12 (3.4%) inpatient, 11 (3.1%) in forensic/prison/court-room settings, 8 (2.2%) corporate/industrial organizational, 3 (.8%) in a laboratory, 1 (.3%) bureaucratic/organizational, 17 (4.7%) other, and 1 (.3%) chose not to respond.

Subjects were sought using state- and national psychological associations, and organizational listserves and websites. The principal investigator sent an invitation email to the executive director of each state psychological association within the U.S. and Canada and requested that they send it to their respective members. Association members who had made their email addresses public via their state association’s domain were sent the invitation email directly. In addition, the principal investigator gathered email addresses from the American Psychological Association’s listserv directory (Psychlink) and sent the invitation to them. Lastly, the principal investigator gathered a list of the APA accredited clinical psychology graduate programs using the APA.org website. The principal investigator then went to each program’s website and compiled a list of the faculty’s public emails listed under clinical psychology and directly sent the invitation email to them. All email invitations included a request to pass the survey along (through email) to colleagues who were similarly credentialed. The e-mail distributed to invited participants described the goals of the study, the importance of the research, the link to complete the informed consent (thus gaining access to the survey), the assurance of confidentiality, contact information of Argosy University’s IRB, and the contact information of the principal investigator.

Procedure:

The internet survey opened with a brief demographic questionnaire and used a combination of forced-choice and fill-in-the-blank items across 3 separate constructs, which included The Maslach Burnout Inventory – Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS), the Self-Care and Lifestyle Balance Inventory, and the Substance Use Screening Inventory. The survey took approximately 15-25 minutes to complete. In order to protect against the same person taking the survey twice, URL’s and/or IP addresses were used by the survey host to identify participation; however, the survey host was asked to remove all identifying information and all URL’s and/or IP addresses were deleted and disembodied from their respective responses prior to data analysis. Therefore, all participation was considered anonymous. Data collection was completed by August 1st, 2011.

Hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: It is hypothesized that there will be a negative correlation between self-care and burnout.

Hypothesis 2: Based on the self-medication theory and gender differences identified in the literature (Weiss et al., 1992), male psychologists who work in high-stress settings, (i.e., private practice, dealing with managed care, community healthcare, and working with forensic populations), will report increased use of self-medication behaviors as compared to their female counterparts.

Hypothesis 3: It is hypothesized that psychologists who endorse burnout will also report some variation of substance use (alcohol, tobacco, caffeine, and/or recreational use).

Hypothesis 4: It is hypothesized that psychologists who endorse the positive items on the self-care portion of the questionnaire related to personal self-reflection fostered by healthy, supportive relationships will report less burnout than those who lack this kind of a positive outlet.

Results:

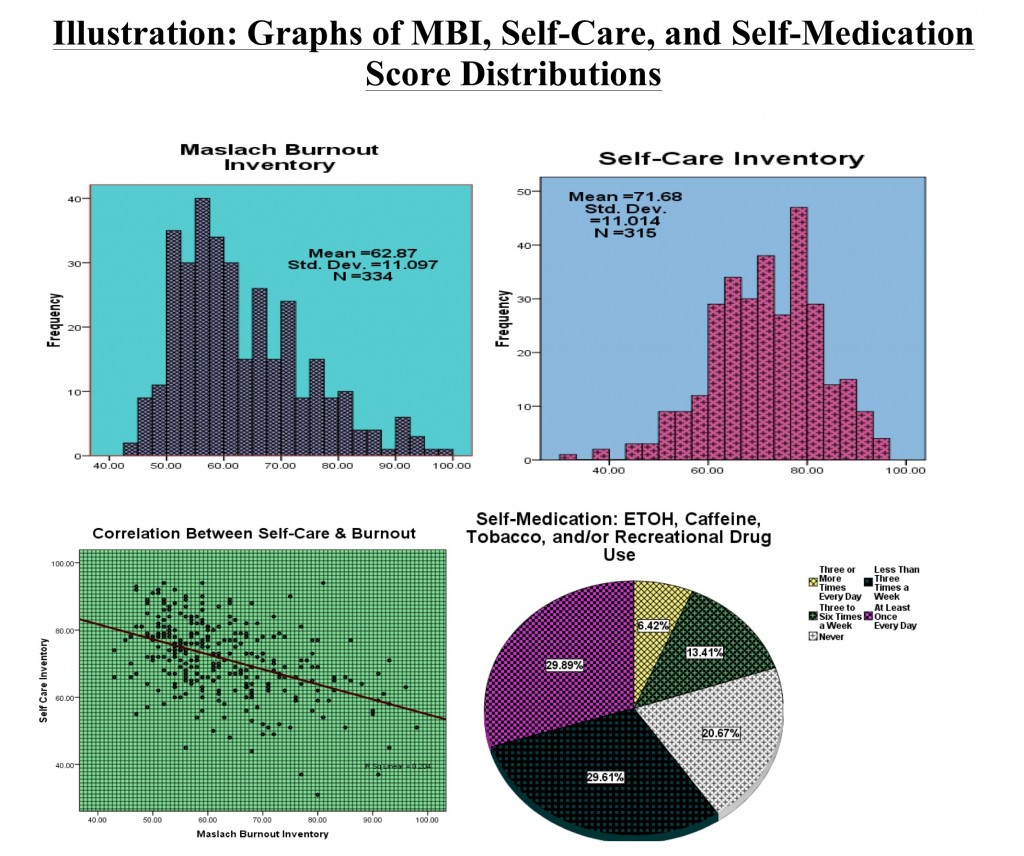

Basic descriptive analyses revealed the following: Scores on the Self-Care Inventory ranged from 31 to 96 (M = 71.67; SD = 11.01). Scores on the Maslach Burnout Inventory ranged from 43 to 98 (M = 62.87; SD = 11.09). Roughly 59% of psychologists reported that they were “very satisfied” with their job, 33.5% reported that they were “satisfied” with their job, 2% reported that they were “unsatisfied” with their job, 1% reported they were “very unsatisfied” with their job, and 3.9% reported that they were “undecided.” In regard to psychologists’ substance use, 20.67% reported “Never” using substances, 29.61% reported using substances “Less than 3 Times a Week”; 13.41% reported using substances “3 to 6 Times a Week”; 29.89% reported using substances “At least Once Every Day”; 6.42% reported using substances “3 or More Times Every day.”

To address Hypothesis 1, a bivariate correlation analysis was used to evaluate the degree of relationship between self-care and Burnout. Simple correlation analysis revealed that Self-Care Inventory scores were negatively related to MBI scores (r = -.45; p< .01), suggesting that as self-care increases, burnout decreases (see scatter plot). Thus, evidence was found to support this claim.

Separate ANOVAs were conducted with gender and stressful work settings as independent variables (IVs) and alcohol use, intoxication by alcohol, caffeine use, tobacco use, and recreational drug use as discrete dependent variables (DVs). For alcohol use, results revealed a marginally significant main effect for gender, F(1, 230)=3.08; p=.08, but no significant main effect for stressful work setting F(1,230)=.83; p=.36. Males reported a mean of 17.44 (SD=45.43) and females a mean of 9.08 (SD=9.27). Interaction between factors was not significant F(1,230)=.34; p=.56. For intoxication by alcohol, the results revealed no significant main effect for gender F(1, 230)=1.45; p=.23, with a marginally significant main effect for stressful work setting F(1,230)=2.86; p=.09. The mean for stressful work settings was .87 (SD=2.54) and the mean of the non-stressful work environment was 1.49 (SD=3.85). Interaction between factors was not significant F(1,230)=.69; p=.41. The additional ANOVAs conducted with gender and stressful work setting as IVs and caffeine, tobacco, and recreational drug as the discrete DVs yielded no main effects, nor was there any interaction effects (all p’s > .25). Therefore, negligible evidence, if any, was found to support Hypothesis 2.

Bivariate correlations were used to evaluate the degree of relationship between MBI (e.g., burnout) scores and self-medication practices (Hypothesis 3). The bivariate analysis revealed no correlation between MBI scores and single use of alcohol (r = -.01; p = .82), caffeine use (r = .06; p = .37), tobacco use (r = -.03; p = .62), and/or recreational drug use (r = -.04; p = .52). However, the bivariate correlation involving burnout and substance use revealed that MBI scores were positively related to intoxication by alcohol (r = .25; p<.01), suggesting that as burnout increases, so does the number of reported instances by psychologists involving intoxication by alcohol.

In response to Hypothesis 4, another bivariate regression was used to evaluate the degree of relationship between healthy, supportive relationships and Burnout. The results revealed that MBI scores were negatively related to activities of self-care involving participation with a healthy support system (r = -.35; p< .01), suggesting that as healthy supportive relationships increase, burnout decreases. Thus, evidence was found to support this claim.

Conclusion:

The anticipated advances in executing this survey includes: Identification of the risk of substance use in psychologists; Identification of the potential risk-factors associated with psychologist impairment; Identification of the specific self-care practices of non-impaired psychologists; and, support for the benefits of self-care practices for those psychologists who present with higher risk for professional impairment.

Self-care should be taken seriously for personal and professional health maintenance. Given the harm that professional impairment can produce, it was practical to assess the variables that can impact and shape licensed psychologists’ practices and their ability to adequately and appropriately cope with stress. The fact that increased self-care practices have the potential to thwart professional impairment, it is imperative to offer psychologists support for the benefits of such practices, especially to those psychologists who practice in higher risk settings. Through acknowledging the value of exercising routine self-care, the proposed objective in presenting this research is to help psychologists restore themselves and flourish both personally and professionally.

Questions for Commentary:

[box] 1. Have you ever experienced signs or symptoms of burnout or known someone who has? If so, what was your experience in decreasing burnout? What seemed to work? What did not?[/box] [box] 2. In your own opinion, what can agencies, organizations, and behavioral health persons realistically do in order to preemptively and proactively decrease and/or prevent burnout?[/box]