Individuals with marginalized identities, such as members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and/or queer (LGBTQ+) community and people of color (POC) are at a higher risk for negative mental health outcomes due to pervasive interpersonal and structural stressors. These stressors include discrimination and violence, expectations of mistreatment, internalized stigma, and identity concealment (Brooks, 1981; Meyer, 2003, 2010). For individuals who hold multiple marginalized identities (e.g., individuals who identify as both LGBTQ+ and POC, or LGBTQ+/POC), systems of power and oppression interact to yield a lived experience that is greater than the sum of its parts, a concept called “intersectionality” (Cole, 2009; Crenshaw, 1989). As a result of intersecting systems of oppression, LGBTQ+/POC are at a higher risk for identity conflict, negative rumination, psychological distress, emotion regulation difficulties, depression, anxiety, substance use, suicidal ideation, and suicide (Diaz et al., 2001; English et al., 2018; Jackson et al., 2020; Jefferson et al., 2013; Meyer, Dietrich, & Schwartz, 2008; Thoma & Huebner, 2013) compared to individuals without multiply-marginalized identities. It is critical to examine how existing systems, including systems that educate mental healthcare providers and facilitate care, reinforce the marginalization of LGBTQ+/POC in the United States.

Individuals with marginalized identities, such as members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and/or queer (LGBTQ+) community and people of color (POC) are at a higher risk for negative mental health outcomes due to pervasive interpersonal and structural stressors. These stressors include discrimination and violence, expectations of mistreatment, internalized stigma, and identity concealment (Brooks, 1981; Meyer, 2003, 2010). For individuals who hold multiple marginalized identities (e.g., individuals who identify as both LGBTQ+ and POC, or LGBTQ+/POC), systems of power and oppression interact to yield a lived experience that is greater than the sum of its parts, a concept called “intersectionality” (Cole, 2009; Crenshaw, 1989). As a result of intersecting systems of oppression, LGBTQ+/POC are at a higher risk for identity conflict, negative rumination, psychological distress, emotion regulation difficulties, depression, anxiety, substance use, suicidal ideation, and suicide (Diaz et al., 2001; English et al., 2018; Jackson et al., 2020; Jefferson et al., 2013; Meyer, Dietrich, & Schwartz, 2008; Thoma & Huebner, 2013) compared to individuals without multiply-marginalized identities. It is critical to examine how existing systems, including systems that educate mental healthcare providers and facilitate care, reinforce the marginalization of LGBTQ+/POC in the United States.

The United States mental healthcare system has an ongoing history of pathologizing, misdiagnosing, and stereotyping both LGBTQ+ individuals (Moleiro & Pinto, 2015) and POC (Hamed et al., 2022; Suite et al., 2007). Presently, LGBTQ+ clinical competencies are not consistently included in graduate curricula (Rutherford et al., 2012), and only a small percentage of providers are trained specifically to address the needs of transgender and nonbinary clients (Whitman & Han, 2017). In addition, providers of color are underrepresented in the United States (Santiago & Miranda, 2014), and many psychological assessments have only been validated for non-Hispanic, White individuals (Manly & Echemendia, 2007; Sayegh et al., 2023). Within the mental healthcare system, LGBTQ+ individuals and POC also report experiencing discrimination, microaggressions, and low quality of care (Constantine, 2007; Howard et al., 2019; Kattari et al., 2017; E. R. Morris et al., 2020), are less satisfied with services compared to cisgender-heterosexual and non-Hispanic White individuals (Avery et al., 2001), and have higher rates of premature treatment dropout (Cooper & Conklin, 2015).

As a field, we are beginning to learn more about the mental health treatment preferences of LGBTQ+ individuals (e.g., Compton & Morgan, 2022) and POC (e.g., Lu et al., 2021). However, reviews of intersectional research focusing on the unique experiences and perspectives of LGBTQ+/POC remain sparse. Therefore, this scoping review aims to synthesize qualitative and mixed-method studies surrounding the mental healthcare experiences and preferences of LGBTQ+/POC in the United States.

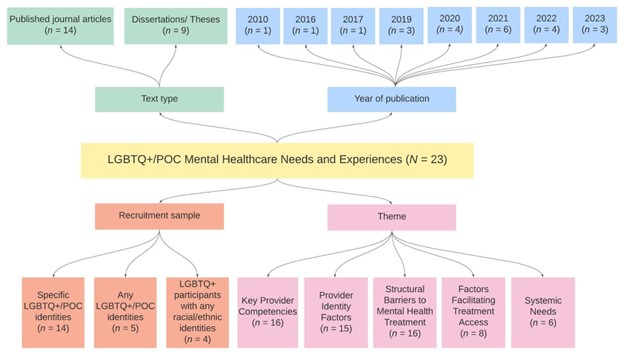

Our search across five databases yielded 1,071 texts, of which 23 met the inclusion criteria. A data map of the included study characteristics is shown in Figure 1. Using thematic analysis, we identified five main themes across the included texts: (1) key provider competencies; (2) provider identity factors; (3) structural barriers to mental health treatment; (4) factors facilitating treatment access; and (5) systemic needs.

Figure 1 (click to enlarge)

- The Key Provider Competencies theme consists of two subthemes: (a) provider knowledge of LGBTQ+ and POC terminology, culture, and experiences and (b) provider awareness of intersectionality. Across studies, LGBTQ+/POC expressed a preference for providers to learn about LGBTQ+ and POC terminology and experiences, rather than placing the burden on clients to teach them. In addition, individuals highlighted the need for providers to understand the concept of intersectionality and create a validating space to discuss identity-related experiences, if clients choose to. Lastly, LGBTQ+/POC preferred when providers arrived at each session without any preconceived notions about the salience of clients’ identities and did not over- or under-emphasize their identities.

- The Provider Identity Factors theme centers the ways in which providers’ identities (e.g., racial/ethnic identity, sexual orientation, gender identity) influence the therapeutic relationship and quality of treatment. Across studies, many LGBTQ+/POC expressed that seeing providers with shared identities created common ground and mutual language, was key to establishing trust in the therapeutic relationship, and made clients feel understood on a deeper level and less like a “chapter in a book”.

- The Structural Barriers to Mental Health Treatment theme consists of three subthemes: (a) cultural stigma and beliefs about mental health, (b) discrimination in mental healthcare settings, and (c) logistical barriers to treatment. Across studies, LGBTQ+/POC described how societal stigma surrounding mental healthcare, expectations and/or experiences of unethical treatment by mental healthcare providers, and practical barriers (e.g., cost, time, provider availability) limited their access to quality care.

- The Factors Facilitating Treatment Access theme consists of two subthemes: (a) social networks and (b) accessibility of resources. Across studies, LGBTQ+/POC highlighted how supportive social environments, educational institutions, religious communities, or LGBTQ+ community organizations can improve access to care.

- The Systemic Needs theme consists of two subthemes: (a) advocating for systemic change and (b) suggestions for services to meet community needs. Across studies, LGBTQ+/POC spoke about the need for educators and clinicians to recognize the mental healthcare system’s roots in racism, heterosexism, and cissexism and advocate for change (including hiring speakers in educational settings with lived experiences of marginalization). Individuals also highlighted the need for more accessible supports which are tailored to the needs of LGBTQ+/POC, are low-cost or free, and bring community members together.

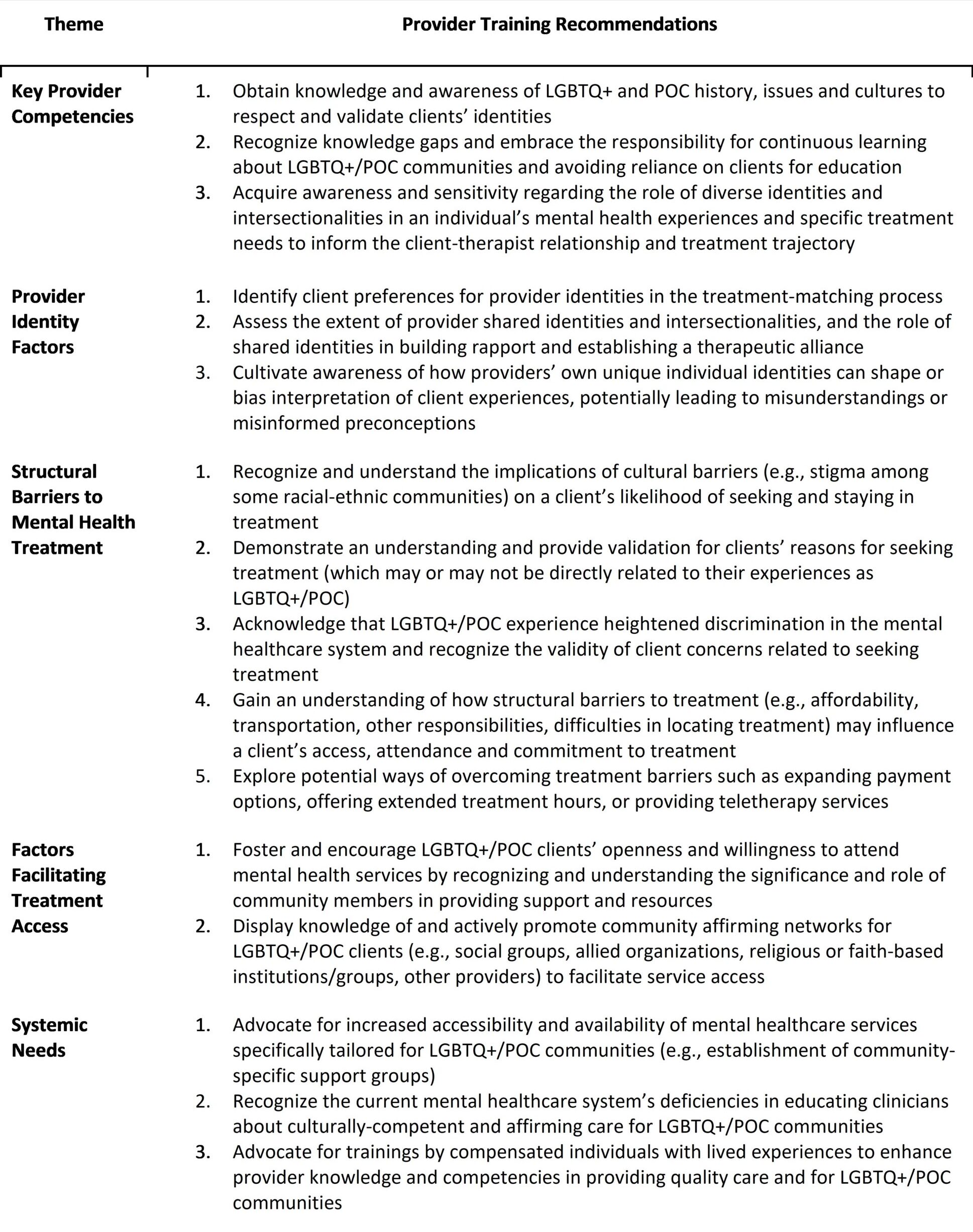

These themes informed 16 training recommendations designed to improve providers’ readiness to deliver identity affirming and culturally responsive care (Table 1). These recommendations are consistent with and complement many existing guidelines for providing quality care for LGBTQ+ and POC communities.

Importantly, these recommendations do not represent the perspectives of all LGBTQ+/POC and should not be treated as a definitive or unchanging knowledge base, which could unintentionally lead to harmful power dynamics or a reliance on stereotypes in treatment (Yan Li et al., 2022). In addition, this review is limited by the overall lack of literature highlighting LGBTQ+/POC perspectives on their mental healthcare experiences, as well as an underrepresentation of specific social identities in the included texts (e.g., individuals who are older adults, transgender men and/or transmasculine, agender, two-spirit, lesbian, asexual, Asian, Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern or North African, Native American, and/or multiracial and related intersections). While systemic changes will ultimately be necessary to improve access to identity affirming and culturally responsive care for LGBTQ+/POC on a large scale, this review aims to offer a preliminary guide for providers and educators to better understand the needs and preferences expressed by LGBTQ+/POC in the United States.

Reference/Target Article

Ito, S.*, Jans, L. K.*, Rosenfeld, E. A., Vilkin, E., Shen, J., Gonzalez, A., & Vivian, D. (2024). Mental healthcare experiences and preferences among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and/or queer people of color: A scoping review of qualitative research and recommendations for provider training. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/cps0000241

Discussion Questions

- What are some common barriers to accessing mental health services for LGBTQ+/POC?

- How can mental health providers better understand and address the unique needs and preferences of LGBTQ+/POC?

- What role does provider training play in improving mental health services for LGBTQ+/POC?

- What systemic changes are needed to improve access to quality care for LGBTQ+/POC?

About the Authors

Sakura Ito, MA (she/her/hers) is a Research Associate at the Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University (Singapore). Her research focuses on digital health and health education, particularly in applying digital technologies to: (1) predict and intervene on mental health issues; (2) improve the accessibility and scalability of mental health services; and (3) enhance the training, education, and practice of healthcare providers. You can reach her at [email protected].

Laura K. Jans, MA (she/her/hers) is a first-year Clinical Psychology Ph.D. student at Stony Brook University. She is interested in the influence of multilevel factors—such as provider and organizational characteristics, treatment elements, and treatment delivery models—on the uptake, accessibility, and effectiveness of mental healthcare for diverse groups. You can reach her at [email protected].

Eve A. Rosenfeld, PhD (she/her/hers) is a Clinical Psychology Researcher at the National Center for PTSD, Dissemination and Training Division at VA Palo Alto and the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University. Her research focuses on harnessing digital interventions such as mobile apps to increase access to evidence-based care for PTSD, particularly for LGBTQ+ Veterans. Through her work, she seeks to serve the communities to which she belongs such as the Latine and LGBTQ+ communities. You can reach her at [email protected].

Jenny Shen, MA (they/them/theirs) is a sixth-year Clinical Psychology Ph.D. student at Stony Brook University and a Clinical Psychology Intern at the UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior. Their research interests include: (1) elucidating the impact of minority stress on mental health disparities among gender and sexual minorities, racial and ethnic minorities, and their intersections; (2) ameliorating the effects of such minority stressors through accessible, transdiagnostic interventions; and (3) identifying implications for clinical practice and policy. You can reach them at [email protected].

Ellora Vilkin, PhD (she/her/hers) is a Postdoctoral Fellow in Gender, Sexual, and Reproductive Mental Health at Montefiore Einstein. She received her PhD in Clinical Psychology from Stony Brook University and completed her pre-doctoral internship at Montefiore Medical Center. Dr. Vilkin’s clinical and scholarly work centers on improving public and scientific understanding and bolstering culturally-responsive treatment in the areas of sexuality, gender, relationships, and sexual/reproductive health. Her research investigates wellbeing among LGBTQ+ people and others with marginalized sexual or relationship practices (i.e. consensual non-monogamy, kink). You can reach her at [email protected].

Adam Gonzalez, PhD (he/him/his) is an Associate Professor in the Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Health at the Renaissance School of Medicine (RSOM) at Stony Brook University (SBU). He serves as the Vice Chair of Behavioral Health, the Founding Director of the Stony Brook Mind-Body Clinical Research Center, and the Co-Training Director of the SBU Consortium Training Programs (Doctoral Externship and Internship, and Post-Doctoral Fellowship). Dr. Gonzalez also leads diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging initiatives at SBU including serving as the Chair of the RSOM Faculty Diversity Ambassadors Council, the Director of Physician & Faculty Well-Being at the RSOM, and the Co-Chair of the Stony Brook Medicine LGBTQ+ Committee. Dr. Gonzalez’s research focuses on the study of traumatic stress and the adaptation and evaluation of stress management programs for various populations. You can reach him at [email protected].

Dina Vivian, PhD (she/her/hers) is a Clinical Professor in the Department of Psychology at Stony Brook University (SBU). She is also the Director of the L. Krasner Psychological Center, the training clinic affiliated with the Ph.D. program in clinical psychology at SBU, as well as the Training Director of the SBU Consortium Training Programs (Doctoral Externship and Internship, and Post-Doctoral Fellowship). Dr. Vivian’s work has focused on issues related to the assessment and treatment of Intimate Partner Violence, validation of psychological treatment approaches for patients presenting with chronic depression and related co-morbidities, as well initiatives designed to increase the dissemination of effective approaches to clinical training (e.g., supervision) and the integration of DEI issues in both training and clinical work. You can reach her at [email protected].

References Cited

Avery, A. M., Hellman, R. E., & Sudderth, L. K. (2001). Satisfaction with mental health services among sexual minorities with major mental illness. American Journal of Public Health, 91(6), 990–991. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.91.6.990

Brooks, V. R. (1981). Minority stress and lesbian women. Lexington Books.

Cole, E. R. (2009). Intersectionality and research in psychology. American Psychologist, 64(3), 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014564

Compton, E., & Morgan, G. (2022). The experiences of psychological therapy amongst people who identify as transgender or gender non-conforming: A systematic review of qualitative research. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 34(3–4), 225–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952833.2022.2068843

Constantine, M. G. (2007). Racial microaggressions against African American clients in cross-racial counseling relationships. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.54.1.1

Cooper, A. A., & Conklin, L. R. (2015). Dropout from individual psychotherapy for major depression: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clinical Psychology Review, 40, 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.05.001

Crenshaw, K. W. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), Article 8. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429500480-5

Diaz, R. M., Ayala, G., Bein, E., Henne, J., & Marin, B. V. (2001). The impact of homophobia, poverty, and racism on the mental health of gay and bisexual Latino men: Findings from 3 US cities. American Journal of Public Health, 91(6), 927–932. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.91.6.927

English, D., Rendina, H. J., & Parsons, J. T. (2018). The effects of intersecting stigma: A longitudinal examination of minority stress, mental health, and substance use among Black, Latino, and multiracial gay and bisexual men. Psychology of Violence, 8(6), 669–679. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000218

Hamed, S., Bradby, H., Ahlberg, B. M., & Thapar-Björkert, S. (2022). Racism in healthcare: A scoping review. BMC Public Health, 22(1), Article 988. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13122-y

Howard, S. D., Lee, K. L., Nathan, A. G., Wenger, H. C., Chin, M. H., & Cook, S. C. (2019). Healthcare experiences of transgender People of Color. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 34(10), 2068–2074. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05179-0

Jackson, S. D., Mohr, J. J., Sarno, E. L., Kindahl, A. M., & Jones, I. L. (2020). Intersectional experiences, stigma-related stress, and psychologi- cal health among Black LGBQ individuals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(5), 416–428. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000489

Jefferson, K., Neilands, T. B., & Sevelius, J. (2013). Transgender women of color: Discrimination and depression symptoms. Ethnicity and Inequalities in Health and Social Care, 6(4), 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1108/EIHSC-08-2013-0013

Kattari, S. K., Walls, N. E., Whitfield, D. L., & Langenderfer Magruder, L. (2017). Racial and ethnic differences in experiences of discrimination in accessing social services among transgender/gender-nonconforming people. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 26(3), 217–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/15313204.2016.1242102

Lu, W., Todhunter-Reid, A., Mitsdarffer, M. L., Muñoz-Laboy, M., Yoon, A. S., & Xu, L. (2021). Barriers and facilitators for mental health service use among racial/ethnic minority adolescents: A systematic review of literature. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, Article 641605. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.641605

Manly, J., & Echemendia, R. (2007). Race-specific norms: Using the model of hypertension to understand issues of race, culture, and education in neuropsychology. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 22(3), 319–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acn.2007.01.006

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

Meyer, I. H. (2010). Identity, stress, and resilience in lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals of color. The Counseling Psychologist, 38(3), 442–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000009351601

Meyer, I. H., Dietrich, J., & Schwartz, S. (2008). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders and suicide attempts in diverse lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. American Journal of Public Health, 98(6), 1004–1006. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2006.096826

Moleiro, C., & Pinto, N. (2015). Sexual orientation and gender identity: Review of concepts, controversies and their relation to psychopathology classification systems. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, Article 1511. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01511

Morris, E. R., Lindley, L., & Galupo, M. P. (2020). “Better issues to focus on”: Transgender microaggressions as ethical violations in therapy. The Counseling Psychologist, 48(6), 883–915. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000020924391

Rutherford, K., McIntyre, J., Daley, A., & Ross, L. E. (2012). Development of expertise in mental health service provision for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender communities. Medical Education, 46(9), 903–913. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04272.x

Santiago, C. D., & Miranda, J. (2014). Progress in improving mental health services for racial-ethnic minority groups: A ten-year perspective. Psychiatric Services, 65(2), 180–185. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201200517

Sayegh, P., Vivian, D., Heller, M. B., Kirk, S., & Kelly, K. (2023). Racial, cultural, and social injustice in psychological assessment: A brief review, call to action, and resources to help reduce inequities and harm. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 17(4), 366–374. https://doi.org/10.1037/tep0000451

Suite, D. H., La Bril, R., Primm, A., & Harrison-Ross, P. (2007). Beyond misdiagnosis, misunderstanding and mistrust: Relevance of the historical perspective in the medical and mental health treatment of People of Color. Journal of the National Medical Association, 99(8), 879–885.

Thoma, B. C., & Huebner, D. M. (2013). Health consequences of racist and antigay discrimination for multiple minority adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 19(4), 404–413. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031739

Whitman, C. N., & Han, H. (2017). Clinician competencies: Strengths and limitations for work with transgender and gender non-conforming (TGNC) clients. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(2), 154–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2016.1249818

Yan Li, A. S., Lang, Q., Cho, J., Nguyen, V.-S., & Nandakumar, S. (2022). Cultural and structural humility and addressing systems of care disparities in mental health services for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color youth. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 31(2), 251–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2021.11.003