Group therapy is an effective means to support positive mental health. It also has the added benefit of being cost-effective, because one clinician can treat many clients at once. However, group therapy facilitation is understudied within psychology, so the evidence-base for how clinicians can lead groups most effectively is limited. In a recently published article, we argue that identity leadership theory can help to address this lack of research, by providing a new and practical framework for understanding effective group therapy facilitation.

What is identity leadership theory?

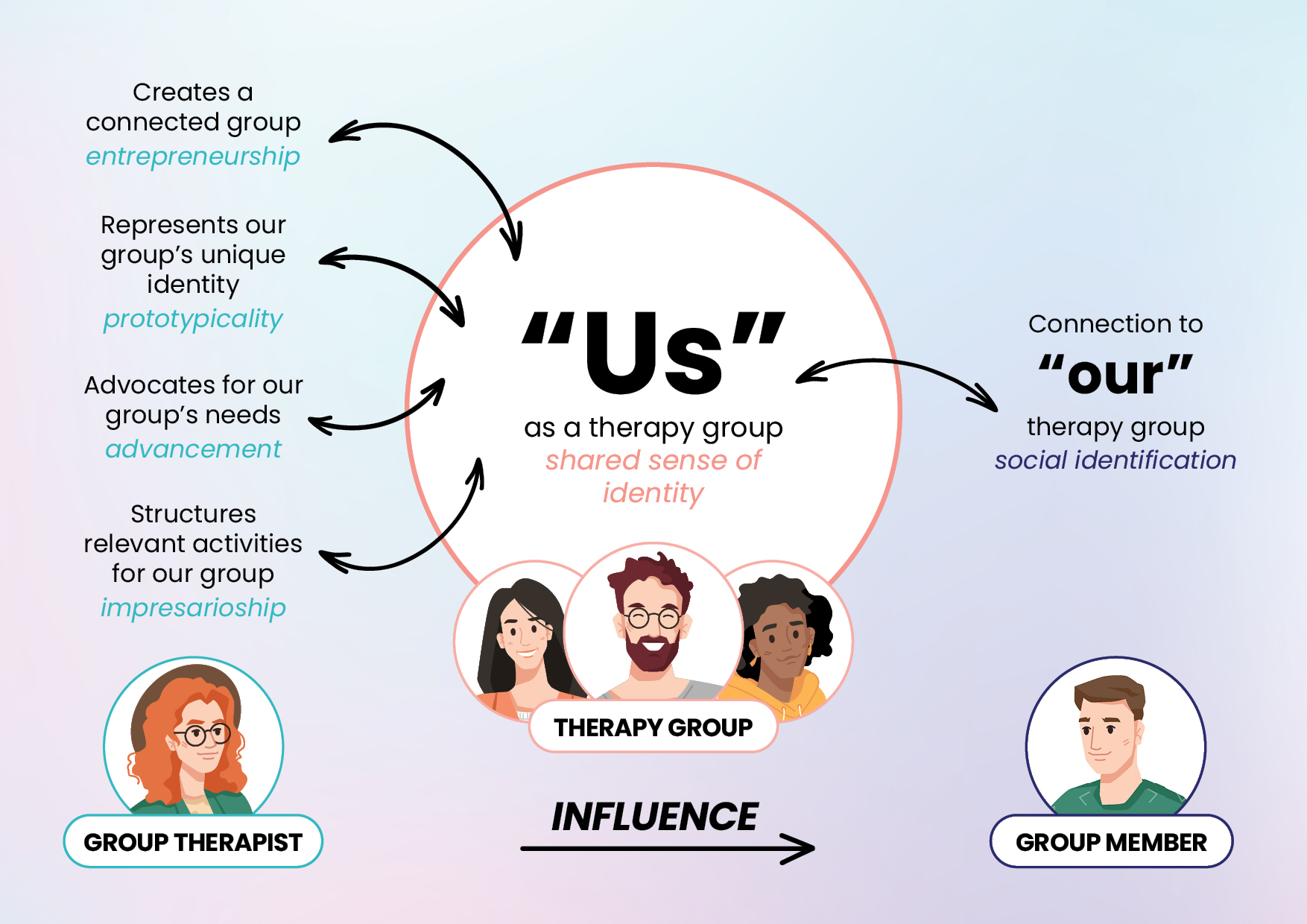

Broadly, identity leadership theory makes two important claims. First, that leadership is a process of social influence, and second, that any individual’s capacity to influence the attitudes and behaviours of other people depends on how well that individual makes these other people feel connected as a group. In the context of group therapy, this second claim primarily concerns how well the therapist can build a shared sense of ‘us’ as a therapy group (Haslam et al., 2020). The idea of exerting influence in a clinical setting may sound unusual (and perhaps even unethical?). However, we argue that this is exactly what clinicians seek to achieve in therapy when guiding individuals to change their thoughts, feelings, and behaviours in ways that improve their mental health.

More specifically, identity leadership theory directs leaders wishing to maximise their effectiveness to engage in four key processes:

- create a strong sense of shared identity among group members (i.e., be an effective identity entrepreneur),

- represent the shared identity of the group (i.e., demonstrate their identity prototypicality),

- advocate for the needs and interests of the group (identity advancement), and

- embed structures, rituals, and activities that allow group members to live out the group’s shared meaning and identity (identity impresarioship).

The figure below depicts how these processes help to create and enhance a sense of ‘us’ as a therapy group. We argue that this shared sense of ‘us’ – a shared sense of identity – holds the key to unlocking several benefits for therapy group members. This is not least because it means that people tend to align their thoughts, feelings, and behaviours with what makes us ‘who we are’ as a group (e.g., ‘we are all here to take action to reduce our substance use’).

What might group therapy identity leadership look like in practice?

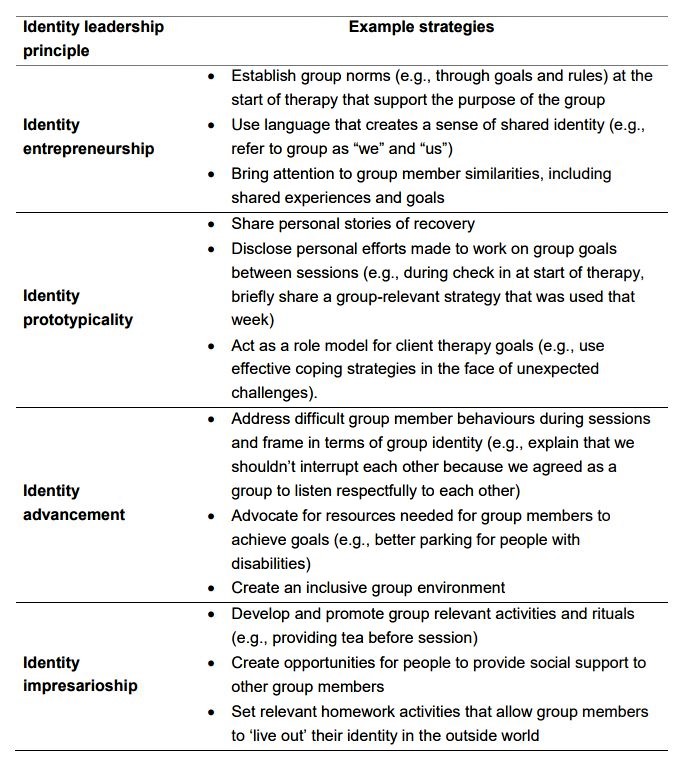

We argue that clinicians already do many of the things that the theory might suggest are beneficial (see Table below).

How might group therapy identity leadership improve clinical outcomes?

Drawing from a range of empirical sources, we outline three main pathways through which group therapists engaging in identity leadership might improve clinical outcomes. Briefly, they are:

- Greater attendance and engagement: A persistent challenge in group therapy is client dropout and inconsistent attendance at sessions. We propose that identity leadership can improve attendance rates by encouraging facilitators to establish and manage positive group norms around attendance. In addition, feeling connected to the group may motivate clients to attend therapy sessions more regularly and to engage in the therapeutic process more actively, as has been demonstrated in sport and exercise contexts (e.g., Stevens et al., 2022). People may also feel less inclined to drop out of therapy (similar to what has been found in work contexts with retention; Steffens et al., 2018).

- Creation of mental health-promoting norms and identities: Positive therapeutic outcomes are more likely when clients internalise new identities that emphasize recovery and empowerment, rather than identities defined by an illness. As identity leaders, facilitators can effectively guide group members in transitioning towards these positive identities, with possible associated benefits for clinical outcomes (e.g., Robertson et al., 2022).

- Promotion of stronger therapeutic relationships: At its core, identity leadership is about building a connection between group members. We argue that attempts to improve this connection will also improve the therapeutic relationship, as has been found in individual therapy (Cruwys et al., 2023; Lee et al., 2023). Given the crucial role that strong therapeutic relationships play in therapy effectiveness, we expect this to yield improved clinical outcomes for group members.

Conclusion

Identity leadership theory provides a new framework for understanding effective group therapy facilitation and paves the way for new research and guidelines. We suggest several ways that facilitators can (and do) engage in identity leadership. We also argue that identity leadership in group therapy may lead to improved clinical outcomes by building attendance and engagement, creating mental health-promoting norms and identities, and strengthening therapeutic relationships.

Target Article

Robertson, A. M., Cruwys, T., Stevens, M., & Platow, M. J. (2023). A social identity approach to facilitating therapy groups. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/cps0000178

Discussion Questions

- What are some of the challenges of incorporating leadership theories into clinical settings?

- What are some other examples of group facilitator behaviors that could be considered identity leadership?

- How else could identity leadership lead to improved clinical outcomes?

About the Authors

Alysia M. Robertson, BPsych(Hons). Alysia is a PhD candidate at the Australian National University. Her research focuses on how healthcare professionals can become more effective leaders. Alysia can be contacted at Alysia.Robertson@anu.edu.au

Tegan Cruwys, PhD. Tegan is an Associate Professor and Clinical Psychologist at the Australian National University. Her research explores how our social relationships affect mental and physical health, particularly for marginalized communities.

Mark Stevens, PhD. Mark is a lecturer at the Australian National University. His research primarily focuses on the social-psychological predictors of health-related behaviors and physical and mental health. He is on Twitter at @MarkStevens2411

Michael J. Platow, PhD. Michael is a professor of Psychology at the Australian National University. His research examines social identity and self-categorization processes, including leadership and influence, prejudice, fairness, education and partisan truth.

References

Cruwys, T., Lee, G. C., Robertson, A. M., Haslam, C., Sterling, N., Platow, M. J., Williams, E., Haslam, S. A., & Walter, Z. C. (2023). Therapists who foster social identification build stronger therapeutic working alliance and have better client outcomes. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 124, 152394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2023.152394

Haslam, S. A., Reicher, S. D., & Platow, M. J. (2020). The new psychology of leadership: Identity, influence and power (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Lee, G. C., Platow, M. J., & Cruwys, T. (2023). Group‐based processes as a framework for understanding the working alliance in therapy. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 23(1), 222–234. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12585

Robertson, A. M., Cruwys, T., Stevens, M., & Platow, M. J. (2022). Aspirational leaders help us change: Ingroup prototypicality enables effective group psychotherapy leadership. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 00, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12406

Steffens, N. K., Yang, J., Jetten, J., Haslam, S. A., & Lipponen, J. (2018). The unfolding impact of leader identity entrepreneurship on burnout, work engagement, and turnover intentions. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(3), 373–387. https://doi.org/10.1037/OCP0000090

Stevens, M., White, S., Robertson, A. M., & Cruwys, T. (2022). Understanding exercise class attendees’ in-class behaviors, experiences, and future class attendance: The role of class leaders’ identity entrepreneurship. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 11(4), 494–508. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000305