Alzheimer’s disease stigma refers to the negative perceptions, attitudes, emotions, and reactions related to Alzheimer’s disease (Corner & Bond, 2004; Werner & Heinik, 2008). Alzheimer’s stigma is a known barrier to early diagnosis, leading people to postpone seeking the care they need, and lowers the quality of life for persons living with the disease and their family members (Corner & Bond, 2004; Werner & Giveon, 2008). What drives stigma reactions? Is it the disease’s symptoms, prognosis, diagnosis, or something else? The answers to these questions are clinically useful as they can aid in interpreting patient reported problems and guide clinical conversations that can improve wellbeing.

Alzheimer’s disease stigma is multifaceted, pertaining to a wide range of negative consequences, such as worrying about structural discrimination, misattributing the severity of clinical symptoms, and antipathetic feelings (S. D. Stites, Milne, et al., 2018). Alzheimer’s disease stigma depends on a signal, which marks a person as a potential target of negative reactions (Corrigan, 2006, 2007). According to the social-cognitive model of stigma, a signal is often a known or assumed hallmark of a disease, such as a symptom or diagnosis. The signal prompts others to apply negative stereotypes, which are cognitive frameworks that give meaning to signals. These stereotypes contribute to affective responses such as pity or fear, and behavioral reactions such as discrimination and social avoidance.

My colleagues and I are finding that there are multiple signals for Alzheimer’s disease stigma. Each can lead to distinct experiences of stigma and require its own clinical conversation. Understanding what aspects of the disease experience signal higher stigma may help clinicians interpret patient symptoms and guide interventions to improve wellbeing.

In this review, I describe a line of research that demonstrates how stigma varies with social and clinical characteristics. I discuss the results with attention to their implications for clinical conversations. It is essential to address stigma as it can discourage a person from seeking diagnosis, hinder a patient’s quality of life, discourage participation in Alzheimer’s disease research, and inhibit members of the public from adequately educating themselves (Alzheimer’s Association, 2011; Alzheimer’s Association & Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013; Connell et al., 2001; Link et al., 1992).

General Framework for Alzheimer’s Disease Stigma

As a condition, Alzheimer’s disease exhibits the five interrelated components that Link and Phelan (2001) argue are important for claiming that a characteristic is stigmatized. Alzheimer’s disease is a 1) human difference that 2) people associate with negative attributes such as poor hygiene and disruptiveness in social situations (S. D. Stites, Rubright, et al., 2018; Werner et al., 2010, 2011). These associations lead persons to 3) separate persons with and without Alzheimer’s into “us” versus “them” categories. For instance, research into “anticipatory dementia” describes significant distress among some older adults that normal memory problems associated with aging are an indication of dementia (Cutler & Hodgson, 1996; French et al., 2012). This indicates that people make distinctions between “us”—older adults who sometimes face memory lapses—and “them”—those with a feared Alzheimer’s diagnosis.

Link and Phelan’s (2001) theory of stigma, modified labeling theory (Link et al., 1989), and the social-cognitive model of stigma (Corrigan, 2006, 2007) contain four assumptions that underpin the conceptual model of stigma. First, a signal, such as a diagnostic label, marks someone as a potential target of negative reactions. Second, the signal prompts others to apply negative stereotype. Third, the stereotypes evoke emotions such as pity or fear, which, lastly, can drive damaging behaviors, like discrimination, ostracism, and paternalism.

Stigma can be understood as the over-attribution and misattribution of characteristics about the disease in ways that inaccurately and prejudicially impact on individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. This interpretation builds from how stereotypes are understood to operate in the stigma experience (Corrigan, 2006, 2007) and from data on symptom attribution in Alzheimer’s disease (Johnson et al., 2015; S. D. Stites et al., 2016; S. D. Stites, Rubright, et al., 2018). For example, due to stigma, a person with mild memory problems might be assumed to have severe memory problems. This has serious implications for all persons with Alzheimer’s disease, including the newest group to be identified in research; persons with preclinical Alzheimer’s disease, who have biomarkers of the disease but do not yet show symptoms. When symptoms begin to emerge, they could experience substantial stigma associated with moderate or severe stage disease.

Recently published scholarship on public stigma of Alzheimer’s disease underscores its insidious nature as a cross-cultural phenomenon (Hagan & Campbell, 2021; Lee et al., 2021; Nguyen & Li, 2020; Rewerska-Juśko & Rejdak, 2020; Werner & Kim, 2021). Because stigma is influenced heavily by stereotypes, the public’s expectations about how the disease affects individuals is an essential element of stigma. Mental illness, for instance, is similar to Alzheimer’s disease insofar as both are expected to have cognitive, emotional, and mental impacts on individuals. Yet, stigma differs in terms of the specific qualities ascribed to these diagnoses; whereas mental illness evokes worries of danger and violence, these qualities are notably absent in Alzheimer’s disease stigma (S. D. Stites, Rubright, et al., 2018).

The Changing Model of Alzheimer’s Disease Care

The first goal of the U.S. National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease is to diagnosis persons with Alzheimer’s disease before the onset of symptoms and then prevent or delay the onset of dementia (Alzheimer’s Association National Plan Milestone Workgroup et al., 2014). To achieve this goal, there have been rapid advances in brain imaging and other biomarkers that can identify proteins associated with early disease in vivo and development of treatments that target those pathologies. Alzheimer’s disease stigma can be a barrier to the success of this newly emerging model of care for Alzheimer’s disease, which requires individuals seek diagnosis and treatment early (S. D. Stites, Milne, et al., 2018).

The emerging biomarker-based definition of Alzheimer’s disease could also shift the character of the stigma associated with the disease, which could negatively affect individuals diagnosed early and their families (Ronchetto & Ronchetto, 2021; Rosin et al., 2020). This has been observed in cancer, where a preclinical diagnosis can be associated with stigma (Scherr et al., 2017) and receiving treatment for that diagnosis can also be stigmatizing (Kenen et al., 2007). Without being accompanied by disease-modifying treatment, Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers convey a risk of developing debilitating cognitive and functional impairments without the ability to alter the disease course.

Jones (1984) highlights disease course as one of six underlying dimensions of stigma and defines it as the “pattern of change over time” persons associate with a condition (p. 24). Changing the course of Alzheimer’s disease with new therapies that can slow the progression pathology may shift public understanding of Alzheimer’s disease from a condition that is terminal to one that is chronic. This, in turn, may also alter the stigma associated with the disease. Advances in cancer research and care, for example, have transformed how the public understands some kinds of cancer. They are chronic rather than terminal conditions (Nakash et al., 2020).

Few studies have examined how stigma associated with an untreatable, terminal disease is affected by the advent of treatment (Chan et al., 2015; Dlamini et al., 2009; Mahajan et al., 2008; Treves-Kagan et al., 2016; Tsai et al., 2013). Treatment might alleviate stigma, or alternatively, negative attitudes about the disease, its causes, and the persons it affects might keep stigma societally entrenched. In HIV, studies have shown availability of treatments have changed but not ultimately eliminated stigma of that disease. One study showed that after 12 months on treatment, individuals’ experiences of internalized stigma decreased by half, and they disclosed their HIV status to a significantly greater number of family members (i.e., from a median of two family members to a median of three at follow-up) (Pulerwitz et al., 2010). Another study focused on public stigma of HIV found that distribution of antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa was associated with some features of stigma decreasing while others increased. For example, researchers found social distancing of persons living with HIV decreased after a treatment was available, but anticipated stigma due to increased social contact was heightened (Chan & Tsai, 2016).

The emerging model of prevention in Alzheimer’s disease has raised a question about the contribution of clinical symptoms to stigma. Clinical symptoms have previously been considered an inherent and immutable part of Alzheimer’s disease and the stigma that can accompany it. In the newly emerging model of care, optimally, Alzheimer’s disease pathology will be identified prior to a person experiencing symptoms and then disease-modifying therapies will slow the progression of that pathology. The goal of the approach is to substantially delay onset of symptoms. Thus, it becomes vital to understand how stigma may affect individuals when clinical symptoms emerge; anticipatory worry about the onset of symptoms and the experience of symptoms could undercut the effectiveness of disease-modifying therapies.

Studies of Public Stigma of Alzheimer’s Disease

My colleagues and I have been conducting a line of research to understand the stigma of Alzheimer’s disease and how advances in biomarker diagnosis and disease-modifying treatment may affect that stigma. To date, we have conducted multiple studies in one of two research samples.

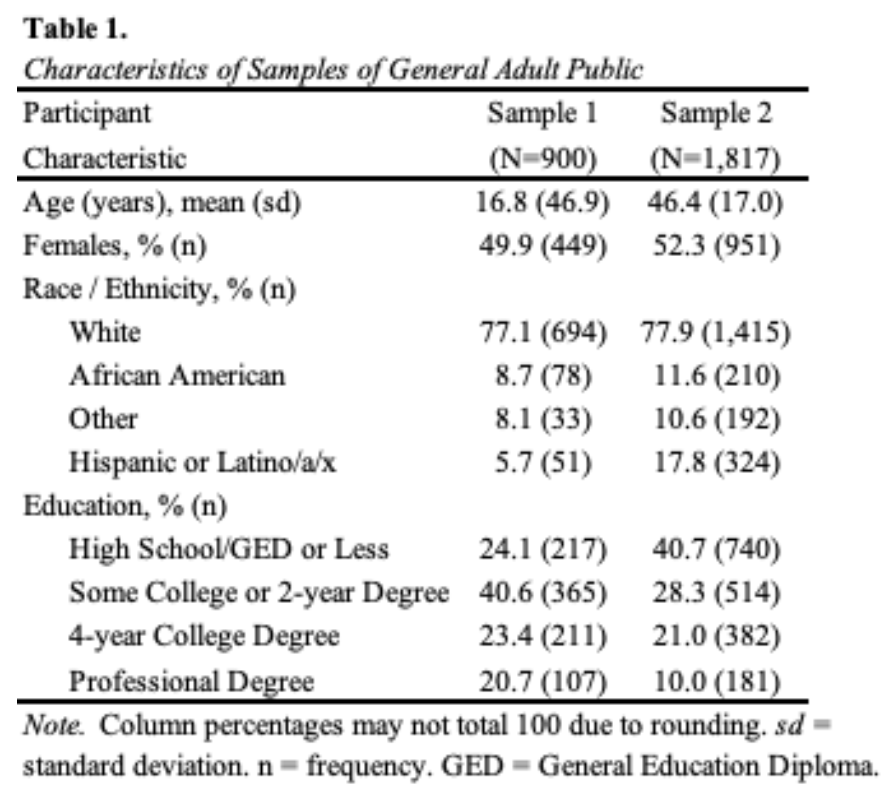

Data collection for the first sample occurred between September 5, 2013 and September 13, 2013. The response rate was 57.4%. The completion rate was 87.3%. The sample had slightly higher educational attainment than the U.S. population, and likely undercounted participants who consider themselves Hispanic (Table 1). In this study, we used a vignette-based experiment that described a person seeking care for memory problems. We varied the person’s diagnosis across three conditions: Alzheimer’s disease, traumatic brain injury, and no diagnosis and prognosis across three conditions: improve, worsen, stay the same (Johnson et al., 2015).

Data collection for the second sample occurred between June 11 and July 3, 2019. The study flow from invitation through analysis is shown in Figure 1 in Stites et al. 2022. The response rate was 63%. The completion rate was 96%. Prior to randomization, participants were asked to complete a comprehension item. Participants read a paragraph about Alzheimer’s biomarker testing and then answered a fact-based question. They were given two opportunities to answer correctly. Participants who failed the second attempt were excluded (n=272).

In this study sample, rather than diagnosis, we varied the fictional person’s biomarker test result between positive and negative (S. D. Stites et al., 2022). We also varied clinical symptom stage across three levels defined by Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) score of no symptoms (CDR 0), mild stage symptoms (CDR 1) and moderate stage symptoms (CDR 2), and treatment availability versus unavailability.

In the sample of 1,817, the mean age was 46 years (95%CI, 46 to 47), which is two years younger than the mean of the U.S. adult population. About half of participants were female (52.3% [95%CI, 50.0 to 54.6]), most self-identified as White (77.9% [95%CI, 75.9 to 79.7]), and most had beyond a high school education (59.3% [95%CI, 57.0 to 61.5]). These percentages are similar to the U.S. adult population (all p>0.05). All demographics were balanced across study conditions. In addition to the base sample, we also collected oversamples of individuals who identified as being 65 years of age or older and those who identified as African American or Black.

In both samples, participants completed the Family Stigma of Alzheimer’s disease scale (FS-ADS), a validated scale that measures Alzheimer’s disease stigma across a range of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral attributions (Werner et al., 2011a). Items on the original assessment were adapted for relevance to the vignettes (Johnson et al., 2015).

The modified FS-ADS is comprised of 41 items that load onto seven empirically derived domains. Items assessed the extent to which the participant believed that the person described in the vignette: (a) should worry about encountering discrimination by insurance companies or employers and being excluded from voting or medical decision making (Structural Discrimination); (b) would be expected to have certain symptoms like speaking repetitively or suffering incontinence (Negative Severity Attributions); (c) should be expected to have poor hygiene, neglected self-care, and appear in other ways that provoke negative judgments (Negative Aesthetic Attributions); (d) evoked feelings of disgust or repulsion (Antipathy); (e) would evoke feelings of concern, compassion, or willingness to help from others (Support); (f) would evoke feelings of sympathy, sadness, or pity from others (Pity); and (g) would be ignored or have social relationships limited by others (Social Distance). Responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale arranged on the screen horizontally from left to right, and analyzed by domain using established methods (Johnson et al., 2015), with higher scores indicating higher stigma.

Participants in both samples were asked “Do you, or have you, considered yourself the primary caregiver of a person with Alzheimer’s?” They selected “yes” or “no”. No definition of “primary caregiver” was provided. We focus on self-identification as it demarcates individuals who view that being an Alzheimer’s disease caregiver is an aspect of their personal identity.

Features of the Emerging Alzheimer’s Disease Model of Care

The model of care for Alzheimer’s disease is changing (Sperling et al., 2014; S. D. Stites, Milne, et al., 2018). In 1906, Alzheimer’s was first characterized based on a clinical symptoms (Yang et al., 2016). Today, Alzheimer’s disease is moving toward a model of secondary prevention, where it is identified via imaging and fluid biomarkers and then treated. Caring for patients’ psychological wellbeing in this model will be essential to reduce barriers to early diagnosis, assure treatment adherence, and optimize individuals’ wellbeing.

Memory Center Setting

A new patient visit at a memory center is a key entry point into the healthcare system for early Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. Stigma is a barrier to accessing Alzheimer’s disease care, including at a memory center. Stigma may differentially affect individuals who are at risk for experiencing disparities in accessing clinical care (Chin et al., 2011; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2013; Lines et al., 2014). To assess this, we compared reactions between self-identified Black (n=1,055) and White (n=1,451) adults who were randomized to a vignette of a fictional patient at a memory center (S. D. Stites et al., 2023). We found Black participants reported higher stigma than White participants on four of seven FS-ADS domains in multivariable models that adjusted for group differences in age, gender, Hispanic ethnicity, and educational attainment (S. D. Stites et al., 2023).

Black participants endorsed higher scores on Structural Discrimination (odds ratio (OR), 1.43, 95%CI 1.22 to 1.67), Negative Severity Attributions (OR, 2.00, 95%CI 1.70 to 2.33), Support (OR, 1.55, 95%CI 1.32 to 1.81), and Pity (OR, 1.48, 95%CI 1.35 to 1.85). Interventions may be needed outside memory centers to aid Black older adults and their family members in seeking out care they may need. In addition, our findings point to specific topics of concern such as worries about discrimination and over attribution or misattribution of symptoms. Opportunities to discuss these issues and identify support networks may help individuals in developing the resources needed to support a decision to seek professional care.

Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosis

In the sample of 900 U.S. adults, we found that prognosis, not diagnosis, caused higher stigma across all seven domains of the FS-ADS (Johnson et al., 2015). Yet, in the sample of 1,817 U.S. adults we found that a positive biomarker test result evoked stronger reactions on all but one FS-ADS domain (Negative Aesthetic Attributions) compared to a negative biomarker result (all p<0.001). The results of these studies are perplexing; why would a biomarker test result affect stigma but a diagnosis would not?

We hypothesize that the contradictory findings may be due to confidence in the biological etiology of the condition. We found in our studies that a positive biomarker result heightens stigma, it also increases confidence in a diagnosis (S. D. Stites et al., 2022, 2023). This is consistent with extant literature that shows attribution of a disease as being physical or biological has been shown to be associated with higher stigma (Weiner et al., 1988).

Our findings emphasize the need to talk with patients and their family members about a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and related testing in order to understand the meaning that individuals place on the information. Interpretation of Alzheimer’s disease test results can be complicated, particularly for individuals who identify with sociocultural groups underrepresented in the research that develops those tests (S. Stites D. et al., 2022). While referral to experts in diagnosis and biomarker testing may be prudent, it is also worth considering whether individuals and their families may benefit from clinical conversations with psychologists that can lend support to identifying salient worries, questions, and cognitive errors.

It may be useful in these conversations to be attentive that stigma has both beneficial and negative consequences. Depictions of Alzheimer’s disease that promote ageism, gerontophobia, and negative emotions (Joyce, 1994; Kirkman, 2006; Van Gorp et al., 2012; Van Gorp & Vercruysse, 2012) heighten stigma by emphasizing negative aspects of the condition (Van Gorp & Vercruysse, 2012). Simultaneously, they evoke attention-grabbing negative emotions that can be effective for motivating certain behaviors– like making financial donations (Van Gorp & Vercruysse, 2012) and risk reduction behaviors (Kessler et al., 2012).

Clinical Symptom Stage

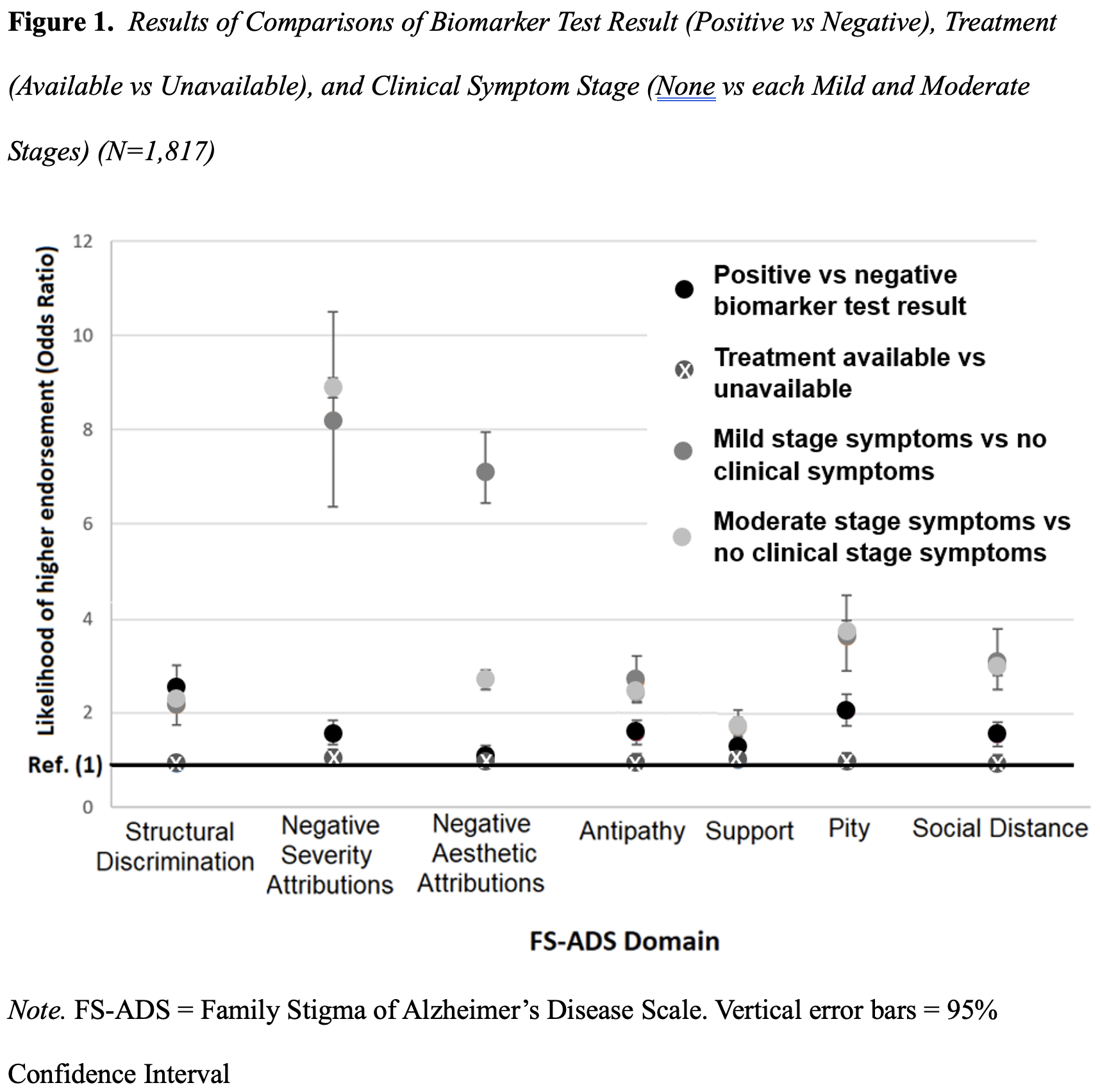

In randomized comparisons we tested whether Alzheimer’s disease stigma differed by clinical symptom stage: no clinical symptoms versus each mild stage symptoms and moderate stage symptoms. We found that participants in the condition describing mild stage symptoms worried about Structural Discrimination (OR, 2.3 [95%CI, 1.9 to 2.8]) and endorsed greater expectations of Social Distance (OR, 3.0 [95%CI, 2.4 to 3.7]) as compared to the condition depicting no clinical symptoms. More participants in the condition with mild stage dementia endorsed harsher judgements of symptoms (OR, 9.7 [95%CI, 7.7 to 12.2]), harsher aesthetic judgements (OR, 2.7 [95%CI, 2.0 to 3.5]), more Antipathy (OR, 2.6 [95%CI, 2.0 to 3.0]), more support (OR, 1.7 [95%CI, 1.4 to 2.1]), and more Pity (OR, 3.9 [95%CI, 3.2 to 4.8]) compared with the condition depicting no clinical symptoms.

We found that comparisons of the condition with moderate stage symptoms to the condition depicting no clinical symptoms showed similar results. In other words, clinical symptoms – be those indicative of mild or moderate stage dementia – lead to similarly elevated levels of stigma (Figure 1). Our findings have a major implication for clinicians talking with patients and families.

While clinicians may differentiate stages of clinical symptoms, adults in the public appear to discern only between the presence versus absence of symptoms. This suggests rigid, black and white thinking that could benefit from education, interrogation, and mindfulness (Bacsu et al., 2022; Corrigan et al., 2012; World Health Organization & Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2012). Intervention could help people identify functioning that they otherwise might overlook and challenge paternalizing beliefs that can lower wellbeing.

While clinicians may differentiate stages of clinical symptoms, adults in the public appear to discern only between the presence versus absence of symptoms. This suggests rigid, black and white thinking that could benefit from education, interrogation, and mindfulness (Bacsu et al., 2022; Corrigan et al., 2012; World Health Organization & Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2012). Intervention could help people identify functioning that they otherwise might overlook and challenge paternalizing beliefs that can lower wellbeing.

Availability of Disease-Modifying Treatments

Given that prognosis drives higher stigma reactions (Johnson et al., 2015), we designed a study to test whether availability of a treatment that slowed progression and thus altered the prognosis of the disease would mitigate stigma. In a sample of 1,817 adults, we randomized them to receive a vignette describing that either a disease modifying treatment was available or unavailable (S. D. Stites et al., 2022). We found that the availability of a treatment that would slow progression of the disease had no measurable influence on any of the seven domains of stigma on the FS-ADS (all ps > 0.05).

The lack of effect of disease-modifying therapies on Alzheimer’s disease stigma was an initially unexpected and disappointing finding. If availability of a disease-modifying treatment cannot alleviate disease stigma, what opportunities are there for anti-stigma interventions? To date, anti-stigma campaigns show mixed effects (Angermeyer et al., 2011; Hanisch et al., 2016; Schomerus et al., 2012; Walsh & Foster, 2021), and better options are needed to mitigate the negative effects of Alzheimer’s disease stigma.

Our findings about clinical symptoms (described in the prior section) might offer a clue to what would effectively reduce Alzheimer’s disease stigma. Those findings suggest clinical symptoms are the most substantive contributor to Alzheimer’s disease stigma (Figure 1) (S. D. Stites et al., 2022). If a treatment could not only slow disease progression but could prevent symptoms, it may aid in lowering stigma.

Findings from our studies also show memory problems are the most salient symptom among those contributing to Alzheimer’s disease stigma (S. D. Stites, Rubright, et al., 2018); about three-quarters of participants (N=317) expected that a person with mild stage Alzheimer’s disease dementia would not remember most recent events (73.8%, 95%CI 65.8 to 82.7). These problems and other clinical symptoms we found to be driving Alzheimer’s stigma might be accurate in later stages of disease but are misattributions in early stages.

Moreover, among the top five most frequently reported aspects of stigma, four did not relate to clinical symptoms but rather related to worries about Structural Discrimination (S. D. Stites, Rubright, et al., 2018). Over half of participants expected a person with Alzheimer’s disease dementia (that is, they show symptoms) would be discriminated against by employers (55.3%, 95%CI 47.0 to 65.2) and would be excluded from medical decision-making (55.3%, 95%CI 46.9 to 65.4). Similarly, high percentages expected the person would have his healthcare insurance limited due to data in the medical record (46.6%, 95%CI 38.0 to 57.2) or have his healthcare insurance limited due to a brain imaging result (45.6%, 95%CI 37.0 to 56.3).

Clinical conversations that encourage patients and family members to critically evaluate current functioning, without catastrophizing worries about problems that might arise later in the disease course, and challenge their fears about the disease may help give wellbeing back to patients living with Alzheimer’s disease and their families. There are also other ways that clinicians can help patients reduce stigma through clinical conversations (S. D. Stites & Karlawish, 2018).

Alzheimer’s Disease Caregiving

As a result of caring for a person with dementia, caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease may have distinct experiences with Alzheimer’s stigma, whereby they witness individuals with Alzheimer’s disease being discriminated against and socially mistreated. They may also experience stigma first-hand given their close association with a person living with Alzheimer’s disease – called spillover stigma. To understand how caregivers’ experiences might differ from others without these experiences, we conducted a study to compare self-identified caregivers (n=82) and non-caregivers’ (n=828) expectations of public stigma experienced by persons living with dementia (S. D. Stites et al., 2021).

We found 9% (n=82) of participants self-identified as a current or former primary caregiver of a person with Alzheimer’s disease, which is about the same as the national estimate of informal caregivers (8.8%). Compared to individuals without this experience, caregivers were more likely to report stronger reactions on all seven domains of the FS-ADS (all p<0.05). Their reactions were attenuated by AD knowledge and being female.

The finding that caregivers reported higher stigma is counter intuitive and raise doubts about current anti-stigma efforts. Common approaches to reducing Alzheimer’s disease stigma, including close interpersonal contact and disease-oriented health education (Batsch & Mittelman, 2012; Goldman & Trommer, 2019; Harris & Caporella, 2014; Kim et al., 2019, 2021; Matsumoto et al., 2023; Tan et al., 2021), are grounded in the idea that greater familiarity with the stigmatized condition reduces the likelihood of stigmatizing individuals with that condition. Caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease are likely to have frequent face-to-face contact and higher than typical disease-oriented knowledge (Garcia-Ribas et al., 2020; Werner & Hess, 2016; World Health Organization & Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2012).

Our findings underscore the importance of addressing Alzheimer’s disease stigma with both individuals living with direct experience of the disease and their family members. The two-pronged approach is needed in order to address wellbeing in both groups. Addressing Alzheimer’s stigma among caregivers is also needed specifically to mitigate harms that might be incurred by the cyclical effects of stigma transferring back and forth in the dyad of patients and caregivers, potentially with compounding ill effects.

Conclusion

Alzheimer’s disease stigma affects millions of older adults and their families. It is essential for all clinicians, particularly psychologists, to understand Alzheimer’s disease stigma and how it varies with lived experiences and clinical characteristics. The information can identify threats to patient and family wellbeing and guide clinical discussions, which may help individuals access care for Alzheimer’s disease sooner and address social, psychological and physical threats to wellbeing. This review summarizes findings from a line of research that demonstrates how stigma varies with the emerging model of Alzheimer’s disease prevention, and discusses the implications of the findings on clinical interactions aimed at addressing patient and family wellbeing.

Author Note

Department of Psychiatry, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, US

Correspondence concerning this article should be sent to Shana Stites, PsyD, University of Pennsylvania, 3615 Chestnut St. Philadelphia PA 19104, United States.

Contact: [email protected]

ORCiD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3994-4343

The author has no conflicts to disclose.

Support

This work was supported by grants from the University of Pennsylvania Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (NIA P30 AG 072979), and the Alzheimer’s Foundation of America (No grant #). This publication is the result of work conducted by the CDC Healthy Brain Research Network. The CDC Healthy Brain Research Network is a Prevention Research Centers program funded by the CDC Healthy Aging Program-Healthy Brain Initiative. Efforts were supported in part by cooperative agreement U48 DP – 005053. The views of this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Stites was supported by the Alzheimer’s Association (AARF-17-528934) and the National Institute on Aging (1K23AG065442, 1K23AG065442-03S1).

References

Alzheimer’s Association. (2011). Alzheimer’s from the frontlines: Challenges a national Alzheimer’s plan must address. https://www.agingresources.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Alzheimers-From-the-Frontlines-1.pdf

Alzheimer’s Association & Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). The healthy brain initiative: The public health road map for state and national partnerships, 2013–2018. Alzheimer’s Association.

Alzheimer’s Association National Plan Milestone Workgroup, Fargo, K. N., Aisen, P., Albert, M., Au, R., Corrada, M. M., DeKosky, S., Drachman, D., Fillit, H., Gitlin, L., Haas, M., Herrup, K., Kawas, C., Khachaturian, A. S., Khachaturian, Z. S., Klunk, W., Knopman, D., Kukull, W. A., Lamb, B., … Carrillo, M. C. (2014). 2014 Report on the milestones for the US national plan to address Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 10(5 Suppl), S430-452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2014.08.103

Angermeyer, M. C., Holzinger, A., Carta, M. G., & Schomerus, G. (2011). Biogenetic explanations and public acceptance of mental illness: Systematic review of population studies. British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(5), 367–372. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.085563

Bacsu, J.-D., Johnson, S., O’Connell, M. E., Viger, M., Muhajarine, N., Hackett, P., Jeffery, B., Novik, N., & McIntosh, T. (2022). Stigma reduction interventions of dementia: A scoping review. Canadian Journal on Aging = La Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement, 41(2), 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980821000192

Batsch, N. L., & Mittelman, M. S. (2012). World Alzheimer report 2012: Overcoming the stigma of dementia. Alzheimer’s Disease International. https://www.alzint.org/u/WorldAlzheimerReport2012.pdf

Chan, B. T., & Tsai, A. C. (2016). Trends in HIV-related stigma in the general population during the era of antiretroviral treatment expansion: An analysis of 31 sub-saharan African countries. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 72(5), 558–564. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001011

Chan, B. T., Weiser, S. D., Boum, Y., Siedner, M. J., Mocello, A. R., Haberer, J. E., Hunt, P. W., Martin, J. N., Mayer, K. H., Bangsberg, D. R., & Tsai, A. C. (2015). Persistent HIV-related stigma in rural Uganda during a period of increasing HIV incidence despite treatment expansion. AIDS (London, England), 29(1), 83–90. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000000495

Chin, A. L., Negash, S., & Hamilton, R. (2011). Diversity and disparity in dementia: The impact of ethnoracial differences in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders, 25(3), 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1097/WAD.0b013e318211c6c9

Connell, C. M., Shaw, B. A., Holmes, S. B., & Foster, N. L. (2001). Caregivers’ attitudes toward their family members’ participation in Alzheimer disease research: Implications for recruitment and retention: Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 15(3), 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002093-200107000-00005

Corner, L., & Bond, J. (2004). Being at risk of dementia: Fears and anxieties of older adults. Journal of Aging Studies, 18(2), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2004.01.007

Corrigan, P. W. (2006). Mental Health Stigma as Social Attribution: Implications for Research Methods and Attitude Change. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 7(1), 48–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.7.1.48

Corrigan, P. W. (2007). How clinical diagnosis might exacerbate the stigma of mental illness. Social Work, 52(1), 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/52.1.31

Corrigan, P. W., Morris, S. B., Michaels, P. J., Rafacz, J. D., & Rüsch, N. (2012). Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: A meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatric Services, 63(10), 963–973. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201100529

Cutler, S. J., & Hodgson, L. G. (1996). Anticipatory dementia: A link between memory appraisals and concerns about developing Alzheimer’s disease. The Gerontologist, 36(5), 657–664. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/36.5.657

Dlamini, P. S., Wantland, D., Makoae, L. N., Chirwa, M., Kohi, T. W., Greeff, M., Naidoo, J., Mullan, J., Uys, L. R., & Holzemer, W. L. (2009). HIV stigma and missed medications in HIV-positive people in five African countries. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 23(5), 377–387. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2008.0164

French, S. L., Floyd, M., Wilkins, S., & Osato, S. (2012). The fear of Alzheimer’s disease scale: A new measure designed to assess anticipatory dementia in older adults: Anticipatory dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27(5), 521–528. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2747

Garcia-Ribas, G., García-Arcelay, E., Montoya, A., & Maurino, J. (2020). Assessing knowledge and perceptions of Alzheimer’s disease among employees of a pharmaceutical company in Spain: A comparison between caregivers and non-caregivers. Patient Preference and Adherence, 14, 2357–2364. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S282147

Goldman, J. S., & Trommer, A. E. (2019). A qualitative study of the impact of a dementia experiential learning project on pre-medical students: A friend for Rachel. BMC Medical Education, 19, 127. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1565-3

Hagan, R. J., & Campbell, S. (2021). Doing their damnedest to seek change: How group identity helps people with dementia confront public stigma and maintain purpose. Dementia, 147130122199730. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301221997307

Hanisch, S. E., Twomey, C. D., Szeto, A. C. H., Birner, U. W., Nowak, D., & Sabariego, C. (2016). The effectiveness of interventions targeting the stigma of mental illness at the workplace: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0706-4

Harris, P. B., & Caporella, C. A. (2014). An intergenerational choir formed to lessen Alzheimer’s disease stigma in college students and decrease the social isolation of people with Alzheimer’s disease and their family members: A pilot study. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias®, 29(3), 270–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317513517044

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Phelan, J. C., & Link, B. G. (2013). Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 813–821. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069

Johnson, R., Harkins, K., Cary, M., Sankar, P., & Karlawish, J. (2015). The relative contributions of disease label and disease prognosis to Alzheimer’s stigma: A vignette-based experiment. Social Science & Medicine, 143, 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.08.031

Jones, E. E. (1984). Social Stigma: The Psychology of Marked Relationships. W. H. Freeman.

Joyce, M. L. (1994). The graying of America: Implications and opportunities for health marketers. American Behavioral Scientist, 38(2), 341–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764294038002013

Kenen, R. H., Shapiro, P. J., Hantsoo, L., Friedman, S., & Coyne, J. C. (2007). Women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations renegotiating a post‐prophylactic mastectomy identity: Self‐image and self‐disclosure. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 16(6), 789–798. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-007-9112-5

Kessler, E.-M., Bowen, C. E., Baer, M., Froelich, L., & Wahl, H.-W. (2012). Dementia worry: A psychological examination of an unexplored phenomenon. European Journal of Ageing, 9(4), 275–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-012-0242-8

Kim, S., Richardson, A., Werner, P., & Anstey, K. J. (2021). Dementia stigma reduction (DESeRvE) through education and virtual contact in the general public: A multi-arm factorial randomised controlled trial. Dementia (London, England), 20(6), 2152–2169. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301220987374

Kim, S., Werner, P., Richardson, A., & Anstey, K. J. (2019). Dementia stigma reduction (DESeRvE): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial of an online intervention program to reduce dementia-related public stigma. Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications, 14, 100351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conctc.2019.100351

Kirkman, A. M. (2006). Dementia in the news: The media coverage of Alzheimer’s disease. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 25(2), 74–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6612.2006.00153.x

Lee, S. E., Hong, M., & Casado, B. L. (2021). Examining public stigma of Alzheimer’s disease and its correlates among Korean Americans. Dementia, 20(3), 952–966. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301220918328

Lines, L. M., Sherif, N. A., & Wiener, J. M. (2014). Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Literature Review. Research Triangle Park.

Link, B. G., Cullen, F. T., Mirotznik, J., & Struening, E. (1992). The consequences of stigma for persons with mental illness: Evidence from the social sciences. In Stigma and mental illness (pp. 87–96). American Psychiatric Association.

Link, B. G., Cullen, F. T., Struening, E. L., Shrout, P. E., & Dohrenwend, B. P. (1989). A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: An empirical assessment. American Sociological Review, 54(3), 400–423. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095613

Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing Stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 363–385. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363

Mahajan, A. P., Sayles, J. N., Patel, V. A., Remien, R. H., Ortiz, D., Szekeres, G., & Coates, T. J. (2008). Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: A review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS (London, England), 22(Suppl 2), S67–S79. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aids.0000327438.13291.62

Matsumoto, H., Maeda, A., Igarashi, A., Weller, C., & Yamamoto-Mitani, N. (2023). Dementia education and training for the general public: A scoping review. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 44(2), 154–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701960.2021.1999938

Nakash, O., Granek, L., Cohen, M., & David, M. B. (2020). Association between cancer stigma, pain and quality of life in breast cancer. Psychology, Community & Health, 8(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.5964/pch.v8i1.310

Nguyen, T., & Li, X. (2020). Understanding public-stigma and self-stigma in the context of dementia: A systematic review of the global literature. Dementia, 19(2), 148–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301218800122

Pulerwitz, J., Michaelis, A., Weiss, E., Brown, L., & Mahendra, V. (2010). Reducing HIV-related stigma: Lessons learned from horizons research and programs. Public Health Reports, 125(2), 272–281.

Rewerska-Juśko, M., & Rejdak, K. (2020). Social stigma of people with dementia. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 78(4), 1339–1343. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-201004

Ronchetto, F., & Ronchetto, M. (2021). Biological diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and the issue of stigma. Journal of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 69(3), 195–207. https://doi.org/10.36150/2499-6564-N327

Rosin, E. R., Blasco, D., Pilozzi, A. R., Yang, L. H., & Huang, X. (2020). A narrative review of Alzheimer’s disease stigma. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 78(2), 515–528. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-200932

Scherr, C. L., Bomboka, L., Nelson, A., Pal, T., & Vadaparampil, S. T. (2017). Tracking the dissemination of a culturally targeted brochure to promote awareness of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer among Black women. Patient Education and Counseling, 100(5), 805–811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.10.026

Schomerus, G., Schwahn, C., Holzinger, A., Corrigan, P. W., Grabe, H. J., Carta, M. G., & Angermeyer, M. C. (2012). Evolution of public attitudes about mental illness: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 125(6), 440–452. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2012.01826.x

Sperling, R. A., Rentz, D. M., Johnson, K. A., Karlawish, J., Donohue, M., Salmon, D. P., & Aisen, P. (2014). The A4 study: Stopping AD before symptoms begin? Science Translational Medicine, 6(228). https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3007941

Stites, S. D., Gill, J., Largent, E. A., Harkins, K., Sankar, P., Krieger, A., & Karlawish, J. (2022). The relative contributions of biomarkers, disease modifying treatment, and dementia severity to Alzheimer’s stigma: A vignette-based experiment. Social Science & Medicine, 292, 114620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114620

Stites, S. D., Johnson, R., Harkins, K., Sankar, P., Xie, D., & Karlawish, J. (2016). Identifiable characteristics and potentially malleable beliefs predict stigmatizing attributions toward persons with Alzheimer’s disease dementia: Results of a survey of the U.S. general public. Health Communication, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2016.1255847

Stites, S. D., & Karlawish, J. (2018). Stigma of Alzheimer’s disease dementia. Practical Neurology, 39–42.

Stites, S. D., Largent, E. A., Johnson, R., Harkins, K., & Karlawish, J. (2021). Effects of self-identification as a caregiver on expectations of public stigma of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease Reports, 5(1), 31–39. https://doi.org/10.3233/ADR-200206

Stites, S. D., Largent, E. A., Schumann, R., Harkins, K., Sankar, P., & Krieger, A. (2023). How reactions to a brain scan result differ for adults based on self-identified Black and White race. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.13558

Stites, S. D., Milne, R., & Karlawish, J. (2018). Advances in Alzheimer’s imaging are changing the experience of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia : Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring, 10, 285–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dadm.2018.02.006

Stites, S. D., Rubright, J. D., & Karlawish, J. (2018). What features of stigma do the public most commonly attribute to Alzheimer’s disease dementia? Results of a survey of the U.S. general public. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 14(7), 925–932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.01.006

Stites, S., D., Vogt, N. M., Blacker, D., Malia, R., Parker, M. W., & The Advisory Group on Risk Evidence Education for Dementia (AGREED). (2022). Patients asking about APOE gene test results? Here’s what to tell them. The Journal of Family Practice, 71(4). https://doi.org/10.12788/jfp.0397

Tan, W. J., Yeo, D., Koh, H. J., Wong, S. C., & Lee, T. (2021). Changing perceptions towards dementia: How does involvement in the arts alongside persons with dementia promote positive attitudes? Dementia, 20(5), 1729–1744. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301220967805

Treves-Kagan, S., Steward, W. T., Ntswane, L., Haller, R., Gilvydis, J. M., Gulati, H., Barnhart, S., & Lippman, S. A. (2016). Why increasing availability of ART is not enough: A rapid, community-based study on how HIV-related stigma impacts engagement to care in rural South Africa. BMC Public Health, 16, 87. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2753-2

Tsai, A. C., Bangsberg, D. R., Bwana, M., Haberer, J. E., Frongillo, E. A., Muzoora, C., Kumbakumba, E., Hunt, P. W., Martin, J. N., & Weiser, S. D. (2013). How does antiretroviral treatment attenuate the stigma of HIV? Evidence from a cohort study in rural Uganda. AIDS and Behavior, 17(8), 2725–2731. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0503-3

Van Gorp, B., & Vercruysse, T. (2012). Frames and counter-frames giving meaning to dementia: A framing analysis of media content. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 74(8), 1274–1281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.045

Van Gorp, B., Vercruysse, T., & Van den Bulck, J. (2012). Toward a more nuanced perception of Alzheimer’s disease: Designing and testing a campaign advertisement. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 27(6), 388–396. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317512454707

Walsh, D. A. B., & Foster, J. L. H. (2021). A call to action: A critical review of mental health related anti-stigma campaigns. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 569539. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.569539

Weiner, B., Perry, R. P., & Magnusson, J. (1988). An attributional analysis of reactions to stigmas. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55(5), 738–748. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.55.5.738

Werner, P., & Giveon, S. M. (2008). Discriminatory behavior of family physicians toward a person with Alzheimer’s disease. International Psychogeriatrics, 20(4), 824–839. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610208007060

Werner, P., Goldstein, D., & Buchbinder, E. (2010). Subjective experience of family stigma as reported by children of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Qualitative Health Research, 20(2), 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732309358330

Werner, P., Goldstein, D., & Heinik, J. (2011). Development and validity of the family stigma in Alzheimer’s disease scale (FS-ADS). Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders, 25(1), 42–48. https://doi.org/10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181f32594

Werner, P., & Heinik, J. (2008). Stigma by association and Alzheimer’s disease. Aging & Mental Health, 12(1), 92–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860701616325

Werner, P., & Hess, A. (2016). Examining courtesy stigma among foreign health care workers caring for persons with Alzheimer’s disease: A focus group study. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 35(2), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621424.2016.1227011

Werner, P., & Kim, S. (2021). A cross-national study of dementia stigma among the general public in Israel and Australia. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 83(1), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-210277

World Health Organization & Alzheimer’s Disease International. (2012). Dementia: A public health priority. World Health Organization. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/75263

Yang, H. D., Kim, D. H., Lee, S. B., & Young, L. D. (2016). History of Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia and Neurocognitive Disorders, 15(4), 115. https://doi.org/10.12779/dnd.2016.15.4.115